Duo is a 12-minutes dance choreography where William Forsythe inquires the logics of harmony held in the pas de deux. The artist questions the canon of this emblematic dance step with the suggestion of its very antithesis. In particular this piece is played by a couple of dancers of same sex, moving on the scene without a dominant role between them and avoiding any kind of physical contact.

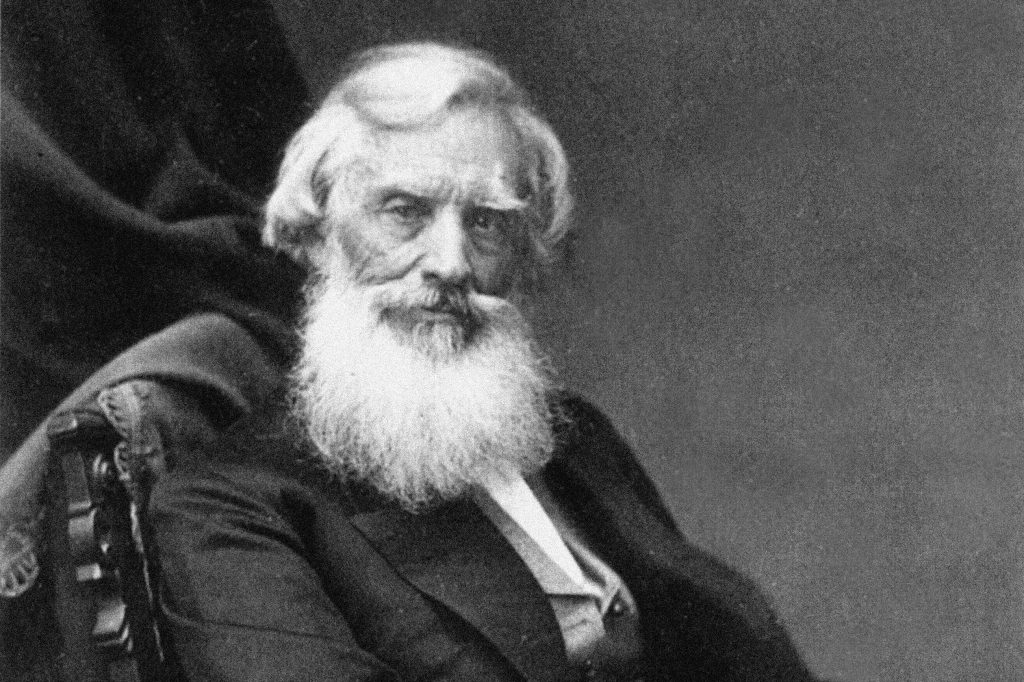

The choreography was composed in 1997 for the Ballet Frankfurt, the dance company that had Forsythe as its director for 20 years making it a landmark for contemporary dance in the nineties for his experimentations on ballet principles. The merit of this great choreographer is his ability to cause an evolution in academic dance, starting from a deep knowledge and passion for this language. His work earned him the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2010.

The basis of this new dance language is, for Forsythe, the counterpoint, consisting in a sequence of gestures composing a dialogue between bodies that describes and defines space and time. Duo includes some variations, strong differences from the academic field, where the synchronic execution of movements is essential: in this work, the choreographic scheme is composed with cues, planned visual signals (between the dancers that assist the coordination of their activity) allowing the dancers to find coordination between their improvisations. At the same time for the viewer the choreographer creates some references based on the culture of ballet: the dancers’ movements can be classified as different, opposed, complementary or, often, specular, and their combination builds symmetries which are the most evident product of the choreographic idea.

The attachment to the academic context is the element that distinguish Forsythe from the contemporary experimentations of France, and it emerges clearly in the selection of professional dancers based on both physical and technical skills for his dance company. Following this principles, the Forsythe Company was born in 2004, after the closure of the Ballet Frankfurt.Today this choreography is a must in contemporary dance repertoire. In this analysis I consider the 2014 performance of the CNN Ballet de Lorraine (you can take a look at it in the video at the end of this article), and it is evident that the attention on the performers’ bodies emerges especially in the moment of the staging: the scenery consists in a black background in front of which the figures of the dancers are clearly visible, lightened by a fixed light; moreover, the choice of a simple transparent leotard as costume underlines the succession of the muscles tensions and relaxations, and emphasizes the athletic training of the dancers, in the clear purpose of enchanting the viewer with the beauty of movements and forms.

Despite the absence of all the key elements of the classic pas de deux, watching Duo the spectator feels clearly, since the beginning, that there is a way in which the two bodies moving on the stage are bound: this is the breath score, the rhythm created by the inspirations and exhalations of the dancers that rules their movements. In fact, the soundtrack composed by Thom Willems for this piece does not constitute the source for the rhythm of the choreography, but it carefully follows its development: the sound gets louder as the two dancers get closer on the stage, and the piano chords underline the moments where their movements find a new unity. This is the element that makes Duo stand out in the panorama of contemporary dance.

Forsythe’s attention for the sound texture created by the dancers’ bodies, which constitutes the ephemeral trace of dance, shows us the importance of attention and sensibility while moving in space. This reflection on the movement of each single dancer in a common space was also the point of We Shall Run, the masterpiece by Yvonne Rainer performed in 1963 by the Judson Theatre. This leading performance piece was a metaphor signifying the value of care and attention towards the other in a democratic system; it underlined the essential fragility in democracy, an including system relying only on the conscience of all its members. As the members of the Judson Theatre were invited to run following the rhythm of the group, free to move in the space and to change directions, with the only score of not crush into the other performers, also in Duo improvisations are included; the dancers can fit their “solo” in the choreography as they know deeply the string of movements, and according to the rhythm of the partner’s breath.

The elevation of the first act of life, breath, to a key element for the understanding of movement in the scenic space is a turning point in Foresythe’s research, that in this way sets its reflection towards a wider field: everyday life. Consciously referring to the work of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, that in the sixties considered the simple and automatic movements of the body as choreographic movements of everyday life, Forsythe aims to show the idea that the space and time in which we live are shaped by the actions we perform: cultural actions, memorised and re-proposed in a spontaneous way.

Forsythe’s choreographic research wasn’t limited to the field of dance: he also considered performance and installations in order to question the relations of man and space; this started in particular with the first collaboration with the architect Daniel Libeskind in 1991. In the last 30 years we’ve seen the success of his numerous choreographic installations, a route that led Forsythe to the ambitious project Choreographic Objects, through which he has presented his reflection also to a general audience and in the context of art museums. Each of these pieces could be the theme of a whole essay, but in this one i can’t avoid mentioning Black Flags (2014), presented in Dresden, and Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, held in Frankfurt between 2015 and 2017.

Forsythe doesn’t stop at the simple analysis of the pas de deux, but with Duo he uplifts it to the status of metaphor of an harmonic and sensitive way of living in the space, that needs attention for balance, distances and signals. Forsythe wants to tell us that, as the pas de deux in ballet, this conscious way of moving should be considered as a canon in every relational space. And after one year of restrictions, I consider this message more and more valid.

So, again, in a world where art only becomes important when its material product is sold for stratospheric amounts of money, the work of research and involvement in the field of the performative arts makes us look at our life with new eyes, makes us aware. For now we settle for a video-registration, impatient for the re-opening of theatres and for the return of this masterpiece of contemporary dance (as many others) on the scenes.