Time was never enough for him…

“Dixeme come se podaria far par no dormir tre ani” (“Tell me how not to sleep for three years”), said Canova to his friend Antonio D’Este when he arrived in Rome, in 1779.

Being taken by “fire and desire” to visit temples, palaces and collections, every morning he waked up at dawn to “hunt” statues and monuments. When he saw the Veiled Christ in the Sansevero Chapel, in Naples, he got speechless for a long time, stunned, and then wrote in his personal diary: “I would give ten years of life to carry out such a beautiful work of art!”. This sort of astonishment for art is a less known aspect of Canova. It should be explored in order to better understand this artist, known until now only through his letters and the many biographies written in the two centuries from his death to the present day.

I believe instead that now is the moment to talk about not just one life, but the many lives of Canova since he had indeed many different characters: an artist, a diplomat, a teacher, a benefactor…

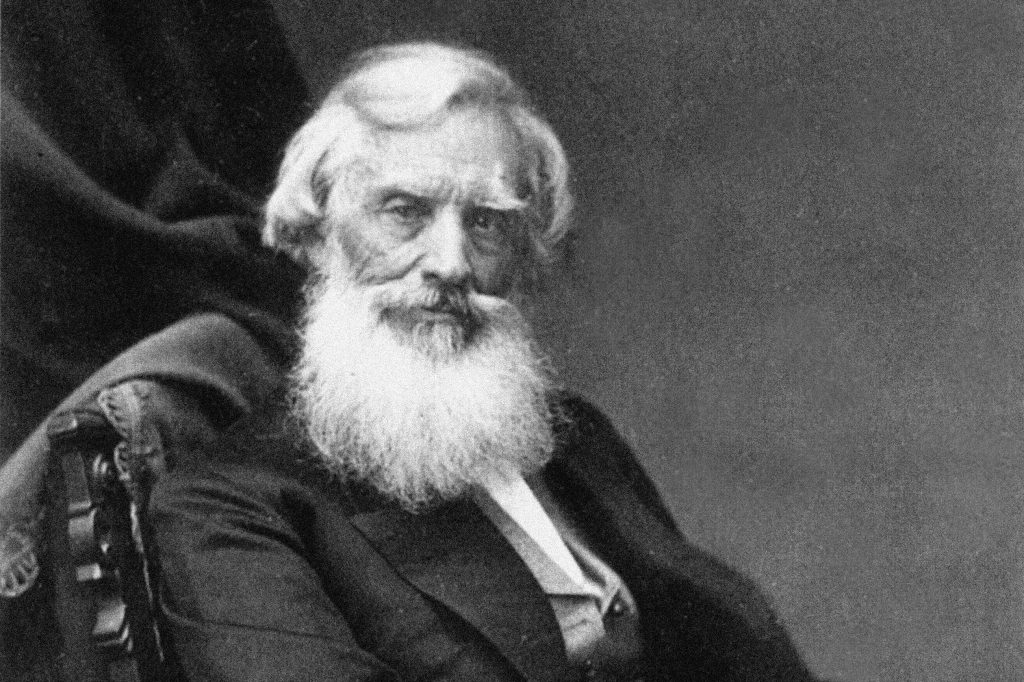

It is well known, for example, that he was reluctant to leave his work: he used to loose sleep for it and neither he interrupted his creation process to have dinner (he used to keep in his workshirt pockets some small pieces of bread that now and then he put in his mouth and chewed slowly). Sometimes, in the evening, still not sated with moulding during the whole day, he even took his oil lamp and went wandering among his plasters, his freshly made clay sketches, his almost finished marbles, and he observed the little flame revealing, through its play of light and shadow, all the mysterious movements of those shapes. He used to get close to the faces, contemplating their glance with the same passion of Pygmalion who fell in love with a statue he had carved himself, being turned into a living woman under Aphrodite’s blessing.

The Canovian method in sculpture was almost obsessive, marked out by the unbridled thrill to transform an idea into matter. His day in his Roman studio did not end with his work. He wanted, instead, “to fully consecrate it to art”. His work was not only a pleasure to him, it was a real mission.

A new portrait of Canova is slowly emerging: a priest of Beauty, capable of renouncing to everything but art. Like every priest, he had in himself something “divine”, as he was defined by Pietro Giordani: he used to follow his rituals, always the same – wake up early, read classical books, mould in silence, go to the theatre; he faithfully used to repeat his methods – drawing, clay, plaster, marble and final touch); his creations soon were converted into universal icons (what is in our thoughts when we imagine Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, or The Three Graces?) His words became aphorisms: “mi no odio nessun” (“I don’t hate anybody”), “i francesi tutti ladri? Non tutti, sire, ma buona parte sì” (“are Frenchmen all thieves? Not all, your Majesty, but a good part” – a pun with the words “buona parte” and Napoleon’s family name Bonaparte)…

When the stomach pain became unbearable, due to immoderate use of the violin drill leaned to his chest, causing him a ribs compression and therefore compromising food ingestion, he had to stop working and getting into bed, because he felt like he was dying. And eventually he’ll die indeed for this pain in his entrails.

In those moments, a lot of friends were anxious about him, martyr for art, and were suffering with him; while they suddenly cheered up when he healed; they wrote him auspicious letters and notes wishing him a speedy recovery, dedicating him congratulation poems.

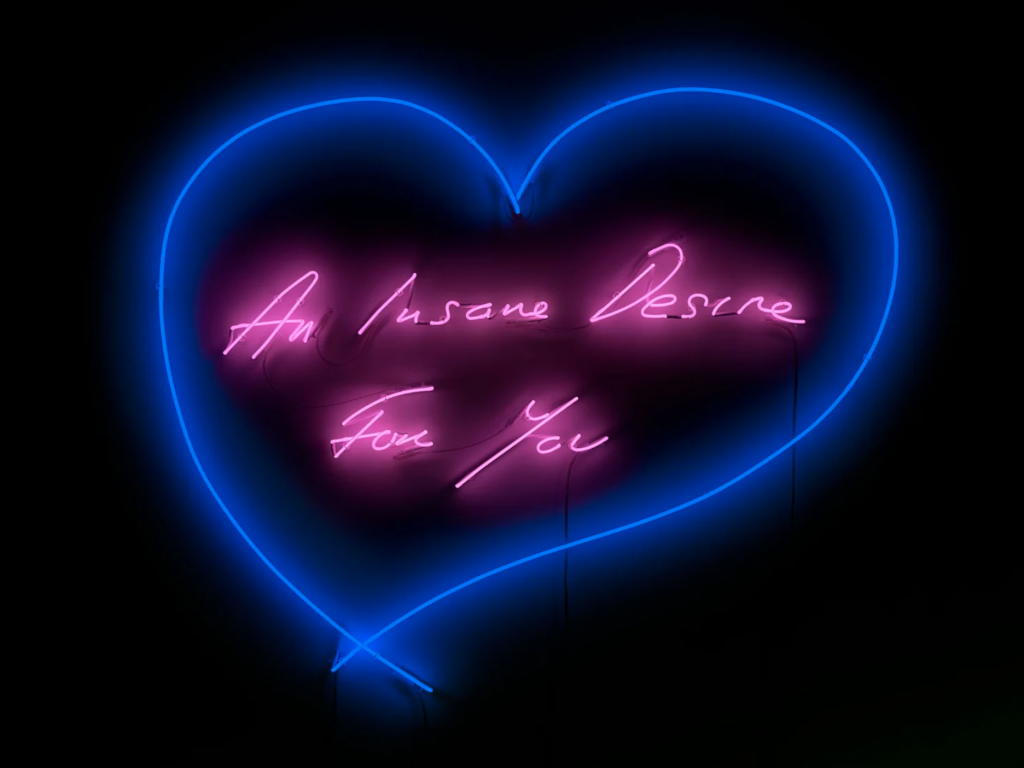

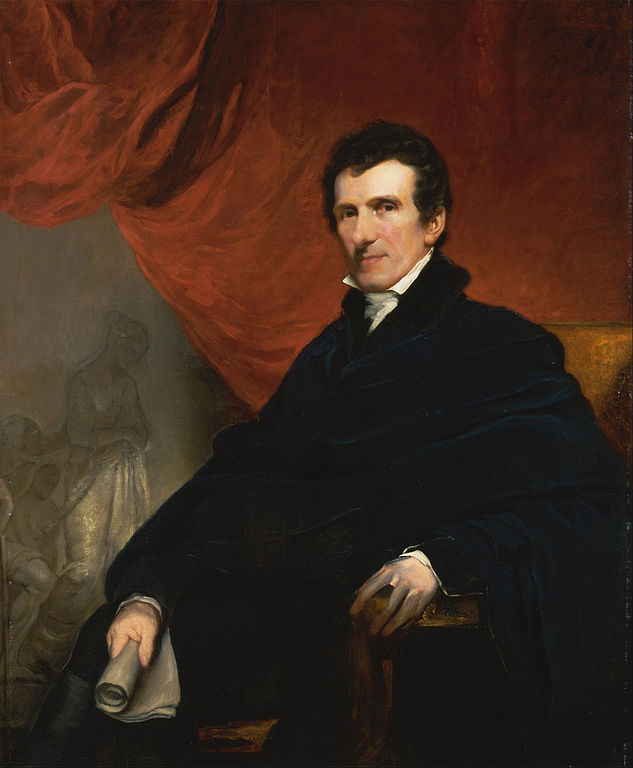

There was around Canova, as for every high priest, an array of followers, artists, colleagues, connoisseurs, professors, collectors and art lovers who were honoured to be his friends, hosted him in every city where he stopped, asked him for copies of his marbles, bought engravings of his works, were proud to portrait him – more than one hundred Canova’s portrait have been registered until now! -, suffered when he was criticized and even counselled him in the making of his works of art, or corrected his project drawings. All these people were increasing and spreading his fame and the knowledge of his statues.

Not to speak about the powerful figures that Canova knew personally (George IV of England, Napoleon Bonaparte, Joaquin Murat, Pope Pius VII…) or indirectly (George Washington, Catherine of Russia…); His multiple missions to Paris, Naples, London, Rome, Vienna, show us an artist capable of moving through the maze of European courts – which, however, he did not love – and smart in presenting requests, pleading causes, obtaining benefits.

We could long continue speaking about Canova’s lives, that still struggle to be known in their complexity; people usually tell anecdotes of his life or just study in detail a single sculpture or analyse a diplomatic mission, but they seldom have consciousness of Canovian “lives”, nor it seems to me that they generally appreciate the universal value of his art. The same happened to Dante, Michelangelo and other universal geniuses: they’ve been left in the hand and in the studies of experts and specialists, but their art is never convincingly filtered towards popular culture. Geniuses attracts but don’t conquer.

I believe that this gap between appreciation and knowledge is due not only, but also to the instruments used until now in spreading knowledge: usually we know an artist through reading biographies, critic essays, catalogues, etc. For example, we do have a series of great biographies about Canova (written by Missirini, D’Este, Cicognara, Malamani, etc.), usually conceived just after his death. They describe the different artist’s “lives” and are very reliable, rich of detail and accompanied by documents, nothing to say about. But they have two limits: they use an outdated language from the 19th century, sometimes very far from today’s speaking, and… they are written. Even more recently published Canovian biographies – the one by Francesco Leone is probably the most complete – are thick, dense and they’re offered to us in a time when reading is a less practised exercise. Maybe it is time for today’s arts, I mean cinema and graphic novels above all, but also short stories and theatre, to be as Pygmalion for Canova: i.e., they should be able to give a new life to this artist, who is often petrified in the mighty biographies of the past.

Antonio Canova, Autoritratto – marmo, Tempio Canoviano, Possagno

Rudolph Suhrlandt, Ritratto di Antonio Canova davanti al modellino della Concordia

Francois Xavier Fabre, Ritratto dello scultore Antonio Canova – 1812, Montpellier, Musee Fabre

Johan Baptist von Lampi, Ritratto di Canova – 1806, olio su tavola, Collezione Principesca, Lichtenstein

Angelika Kauffmann, Ritratto di Canova – 1795, olio su tela, Padova (collezione privata)

Thomas Lawrence, Ritratto di Antonio Canova – 1815-1819, olio su tela, Museo Gypsotheca Antonio Canova, Possagno