“Durante i secoli dell’Evo Medio, come il filosofo e il credente aspirano all’assoluto, così l’artista volge la sua ricerca al generico.”

Luigi Coletti’s words form the perfect historical-critical framework of Tomaso da Modena’s artistic career. A description of the art of the Middle Ages not as an anthology of particulars, but as an expression of the generic in order to overcome particulars. In this period artistic language goes through a long process of moving away from apparent reality for the establishment of an ascetic art, so we can speak of a real metaphysical art aimed at ideography, that is, the drawing of an idea.

Around the 12th century a profound social change took place that was destined to spill its impact on the cultural level as well: the Commune was born and with it a new social class, the bourgeoisie, was defined; there was a great fervor of works of art; St. Dominic and St. Francis founded the mendicant monastic orders, which had a powerful impact on the population of the faithful. Henry Thode in 1885 published a work entitled: St. Francis of Assisi and the Beginnings of Renaissance Art in Italy,the central thesis of which wants Francis to be representative of the bourgeoisie just emerging into history, the first individual to establish himself as such, and who by his proselytizing ability inaugurated an art for all. Through St. Francis, then, the whole European world was refreshed and renewed; a new sense of realism pervaded art and set it on new paths. Not surprisingly, he further specified:

“From Giotto to Raphael, there is a unified movement: and what is common in all this movement, namely a conception that places religion and nature in harmonious consonance, has its roots in Francis of Assisi.”

t begins in Francis a protagonism of individuality that, prior to Humanism, found supporters exclusively in Giotto and Tomaso da Modena (it is a suggestive element that our Tomaso da Modena was born in 1326 or exactly one hundred years after the death of the Assisian). From the gilded backgrounds of medieval icons, artists, in order to interpret the new protagonist of the social scene (the bourgeoisie) must bring “their feet back on the ground” and mimetically represent the real world, everyday life: naturalism, pragmatism is the intrinsic nature of the bourgeoisie. More than a century will be needed for the full maturation of the phenomenon, which will gradually come to fruition from fifteenth-century Humanism to the sixteenth-century Renaissance.

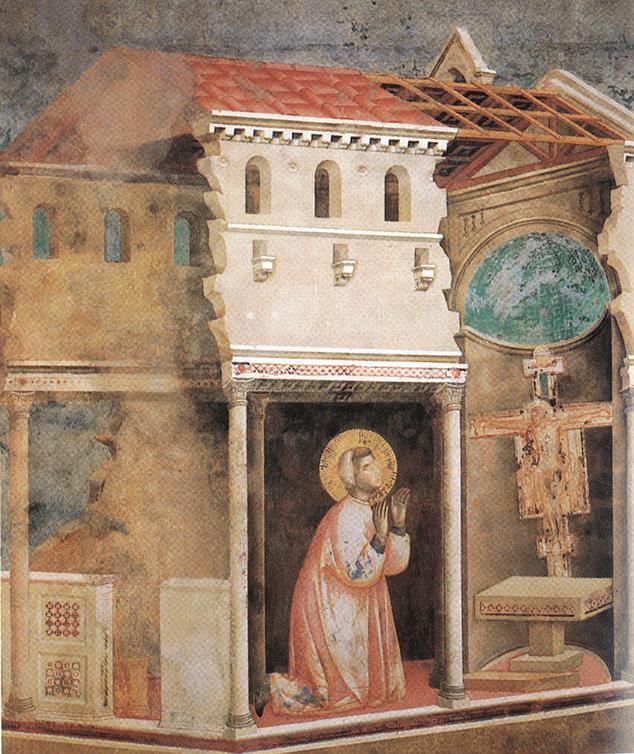

Turning our gaze strictly to the art sector, the absolute star of the 13th scene becomes a Tuscan, whose name needs no further introduction: Giotto of Bondone. Giotto’s spatial management, with the introduction of perspective vision, is of an ethereal and perfect balance, but, concentrating on observing the faces of the characters, we are compelled to note how they, while taking on the consistency of flesh-and-blood bodies, remain to be personae, that is, masks in a setting.

It is only with Tomaso da Modena that, for the first time, the veil of idealization is broken through in order to savor bare, stark reality, but let us get to know this avant-garde and ill-fated artist directly.

Tomaso Barisini was born in Modena between 1325 and 1326 to the painter Barisino dei Barisini, and the air he breathed as a young man, initiated into art probably by his father, was that of the Bolognese painting of Vitale da Bologna. The latter had assimilated Giotto’s lesson metabolized through the filter of the generations of Rimini painters who had worked on the site Giotto had set up in Rimini for the pictorial cycle in the Church of San Francesco ( now better known as the Malatesta Temple). Very uncertain, however, is what remains for us of Tomaso’s early period.

Some documents testify that on January 9, 1349 Tomaso was in Treviso , where his brother Benedetto had recently died (probably struck by the plague). Indeed, here, in the chapter house of the Dominican convent of San Nicolò, is a work signed and dated by the painter. The identifying inscription, found next to the inner hinge of the room’s doorway, reads:

“Anno Domini MCCCLII prior tarvisinus ordinis predicatorum depingi fecit istud capitulum et Thomas pictor de Mutina depixit istud.”

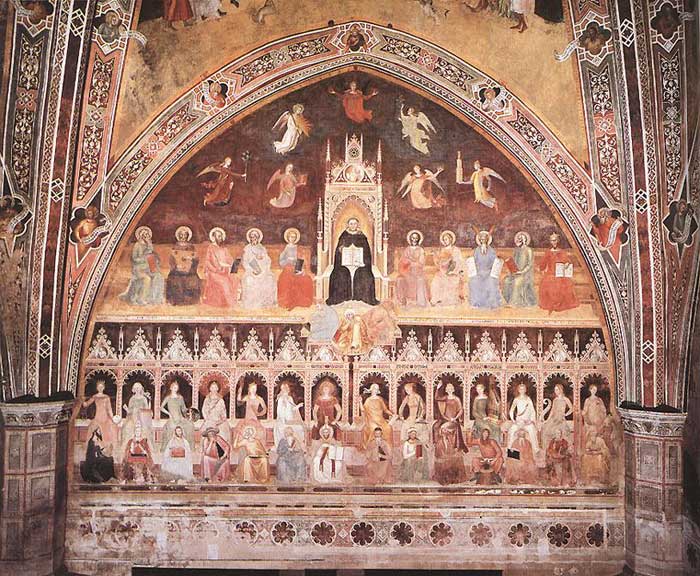

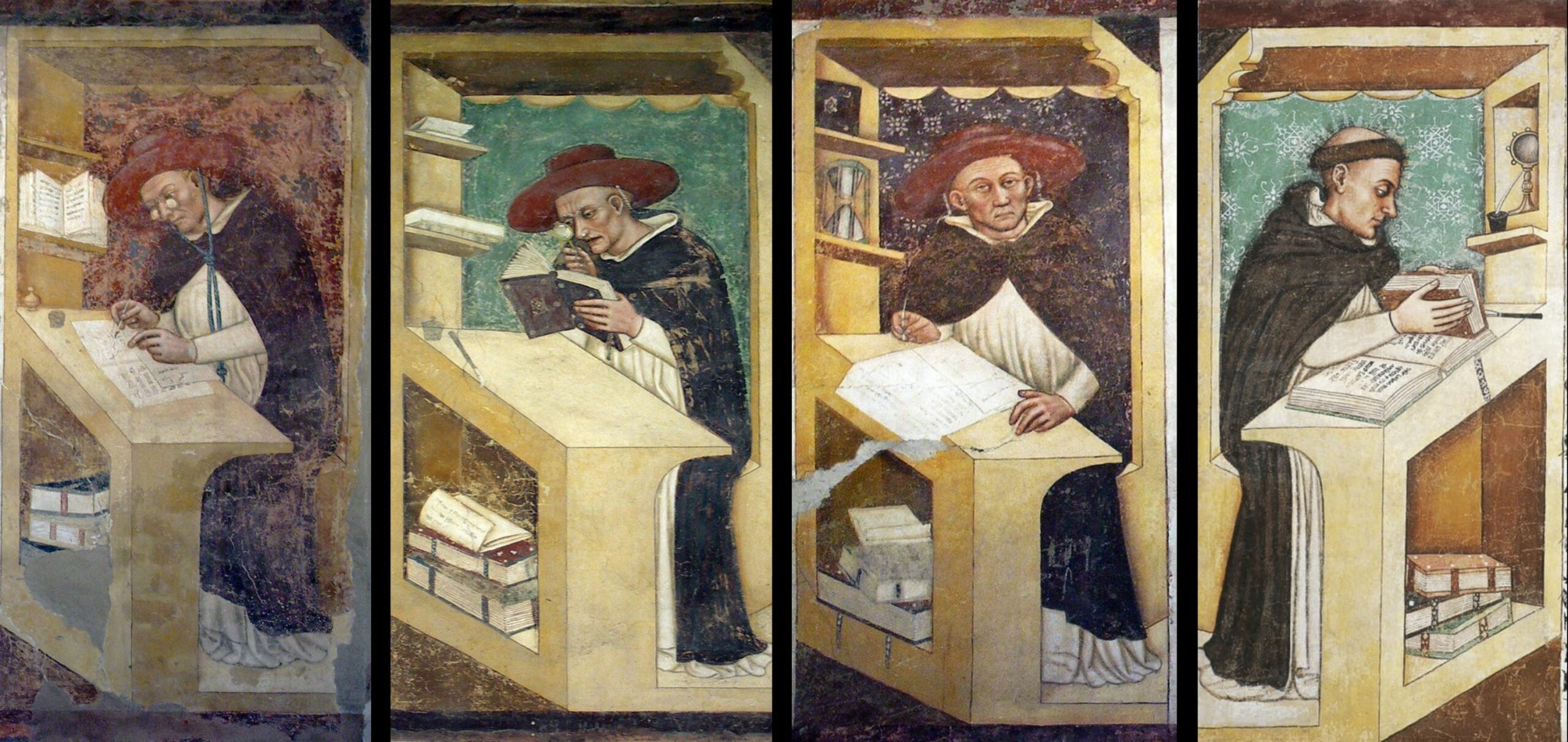

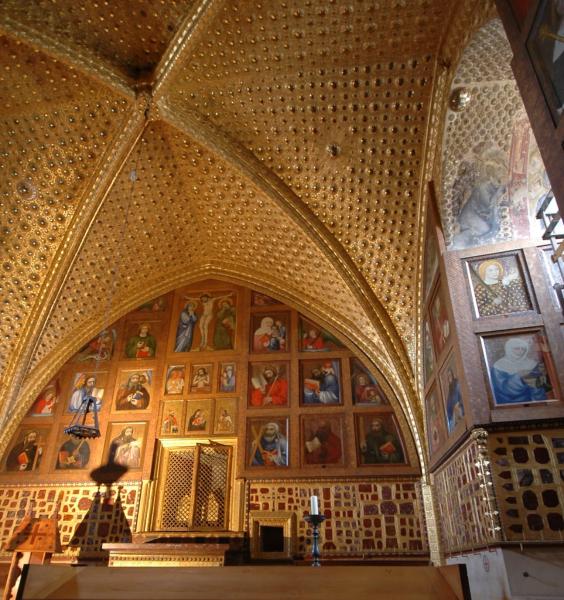

This is considered the masterpiece of Tomaso da Modena’s art. The convent of San Niccolò is located on the southwestern edge of the city, next to the church of the same name, and became, beginning in 1840, the seat of the bishop’s seminary. Following the eastern portico of the convent complex’s minor cloister, one comes to a large pointed-arch portal flanked by two Romanesque double lancet windows; crossed this threshold, one is plunged into a timeless environment. Between the two long, narrow windows of the wall we face is a Crucifixion with the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, from the second half of the 13th century. Also by the same hand is the frieze with plant motifs placed under the wooden beamed ceiling. Tomaso was commissioned to execute a new pictorial cycle on the side walls of the chapter house. The commission came from the prior, Fra Fallione da Vazzola, and from the provincial father Fra Francesco Massa, who lived in the convent and hoped to host, in 1352, the General Chapter of the Order there (a hope that went unfulfilled). The theme of the glorification of the Dominican order was chosen for the pictorial cycle; Tomaso made the representation without resorting to symbolic elements, such as those found in the famous Spanish chapel in Santa Maria Novella in Florence by Andrea di Bonaiuti from 1356-1368, he instead created a small Dominican encyclopedia: a lineup of forty illustrious friars, each in his own studiolo, flanked by captions containing a concise list of the works of the studiolo’s owner.

Forty monks, then, in two series branching off from the middle of the back wall, that is, from the crucifixion, toward which they are facing. Exceptions are only three figures, those of the canonized saints: Dominic, Thomas Aquinas and Peter Martyr, which are in the eastern corner, that is, to the right of the Crucifix; they are placed in perspective: they face directly toward those in the room. Unfortunately, these have come down to us in a poor state of preservation. Tomaso da Modena escapes the risk of repetitiveness of the representation with the variation of the attitudes and expressions of the subjects. There are those who point, those who read, those who collect and compare, those who write, those who meditate, those who blow on the tip of the calamus, those who pin the stylus, those who line the page. Following the rhythm of the hands we find those who wonder, those who pray, those who follow the thread of reading, those who rest their heads on it meditatively. Finally, we find in the cells particular objects that had never before been represented in painting: the glasses worn by Cardinal Hugh of Provence, the lens that Cardinal Nicolas de Rouen uses to read, the hourglass of Cardinal William of England, the mirror of Brother Isnard of Vicenza. It is the entry of the real into art. It is the entry of the real into art.

It is a novelty and strength, that of Tomasesque language, that we also find in his other Treviso works: from the column in the same church of San Nicolò, to the angels of the Madonna in Santa Lucia, from the fresco of the Giacomelli Chapel in San Francesco to the second peak of the Stories of St. Ursula in Santa Margherita.

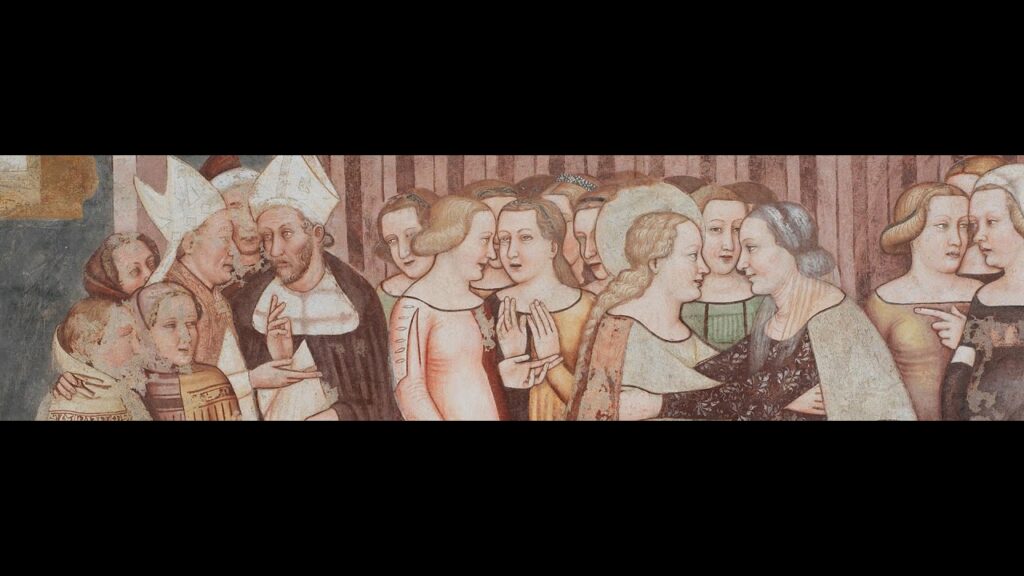

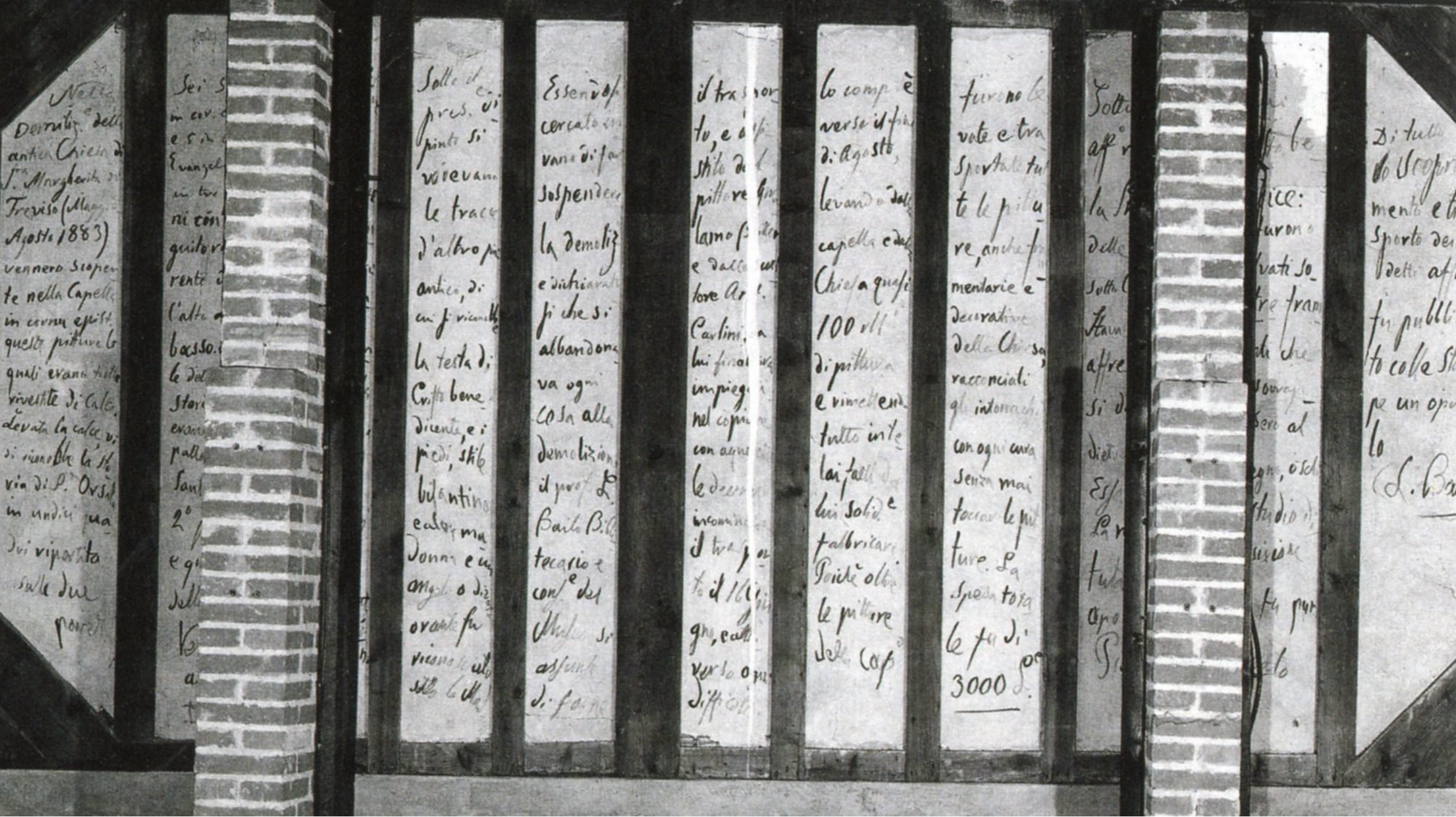

The latter cycle has a complex history. First, it is neither signed nor dated, so , if the stylistic attribution to Tomaso is not questioned, it can be placed between 1355 (after the completion of the Dominican cycle) and 1358 (when it is documented in Modena in a notarial deed). Second, it is a detached cycle of frescoes. The adventurous story of the work began in 1883, when the church of Santa Margherita, in the face of Napoleonic expropriations, was decemanized and turned into a riding school: promptly Luigi Bailo, assisted by Girolamo Botter and Antonio Carlini, intervened to save the works on the church walls, which were detached, and thus the cycle became part of the civic collections.

Luigi Bailo was a protagonist of the Treviso cultural scene for nearly a century, promoting the spread of culture, understood as an indispensable tool for the moral and civic growth of the nation and in particular of the city of Treviso. In 1862 Bailo decided to leave the Treviso seminary to enroll in the Faculty of Philosophy in Padua, taking courses from Pietro Canal and Andrea Gloria. He returned to Treviso in 1865 and put himself at the service of his city by engaging in a variety of educational and popular activities: he was a Greek teacher at the Liceo di Stato for fifty years and contributed to numerous local periodicals. In 1878 he was appointed librarian of the Municipal Library of Treviso, initiating a reorganization of the city’s cultural institutions that culminated in the founding of the Treviso Civic Museum, drawing inspiration from the layouts of the most innovative Italian museums. The entry of a first nucleus of works, following the adventurous detachment in Santa Margherita in 1883 that we have mentioned, forced the municipal authorities to grant Bailo new exhibition space for the museum.

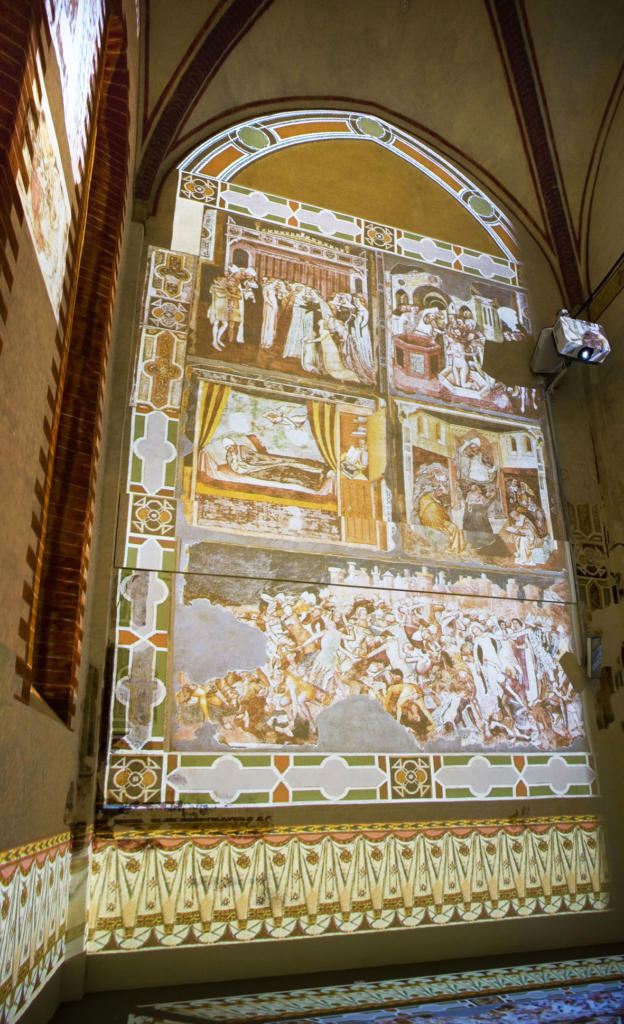

A museographic intervention is currently being planned to give a new layout to the cycle, which today is located in the church of St. Catherine and is presented with a layout from the late 1990s that not only occupies the entire conference room into which the nave of the church has been converted today, but is at the same time arranged in a way that does not respect the narrative order.

Equally adventurous is the story the cycle tells: the life of St. Ursula, which is faithfully depicted following the text institutionalized in Jacopo da Varazze’s (or da Varagine’s) La Legenda Aurea. Ursula, the daughter of a king of Britannia who had consecrated herself to God, was asked for marriage by a pagan king advised by a vision she had in a dream, Ursula, against her father’s wishes, accepted the marriage on the condition that the groom be baptized. She then set out with eleven thousand companions (according to some versions, also with the betrothed) and in the company of Queen Hierosina, her mother, and sisters, on a pilgrimage to Rome, where she was received by Pope Cyriac (a personage unknown to history); during Ursula’s Roman sojourn, an angel appeared to Pope Cyriac in a dream, inviting him to abandon the papal seat and follow Ursula on her return journey to Britain The pilgrimage passed through Cologne, which had just been conquered by Attila: the Hun king asked Ursula to marry him, but this she refused him: thus the scourge of God killed her and all her retinue.

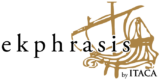

The cycle is characterized on a formal level by a plastic narrative of extreme refinement and elegance, the common thread of which is the use of gold foil on the embroideries of the fashionable dresses worn by the women in Ursula’s procession, which are faithful to those actually worn in the courts of the 12th century. Each scene follows one another according to a masterful theatrical direction in which the actors are required to have a strong psychological and expressive participation of everyday naturalness expressed by means of contrite looks and marked gestures with a vivid narrative effectiveness that engages and captures the viewer in a crescendo leading from the undressing of the man in the foreground in the episode of the Prince’s baptism to the sad epilogue rendered with intense and recomposed drama.

Tomaso da Modena is a painter who in italy remains on the margins of medieval art history; he is more studied beyond the Alps for works that link him to Emperor Charles IV and the Castle of Karlšteinc-as a personality whose modus was not followed, but we can consider him an avant-gardist of psychologism, truth and “motions of the soul.”

To close the circle, we return to quote Luigi Coletti’s descriptive density:

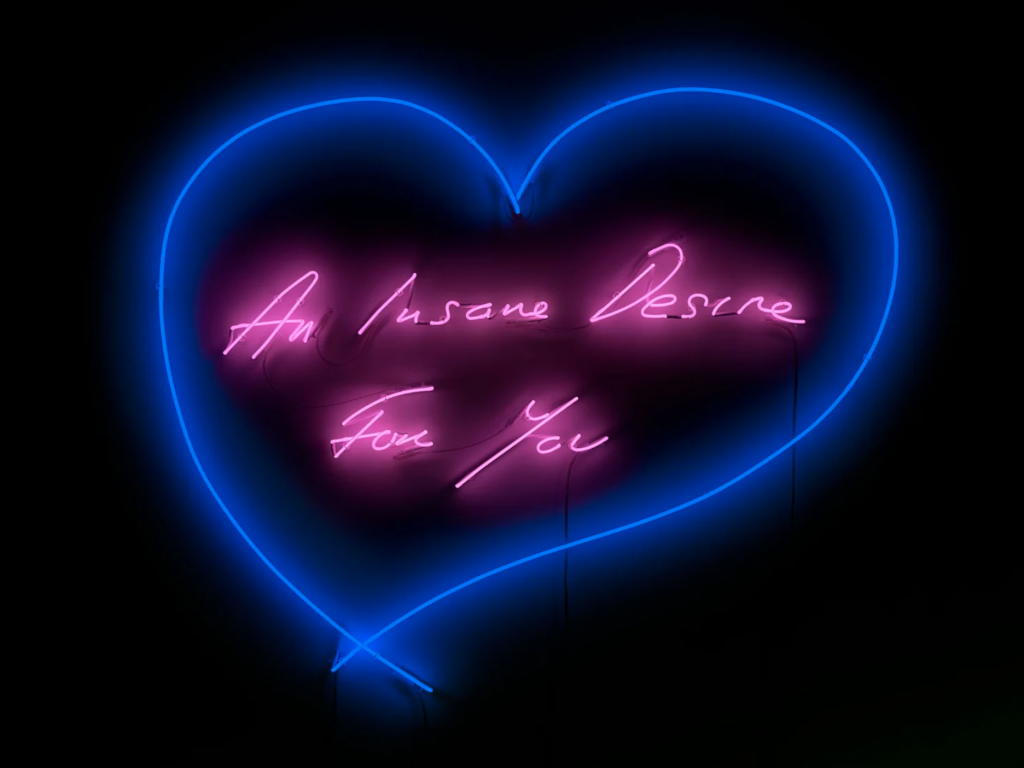

“Con Giotto era stata la conoscenza; coi Senesi, il capriccio; coi Bolognesi, l’appetito. Ma, con Tomaso di Modena, è l’amore.”