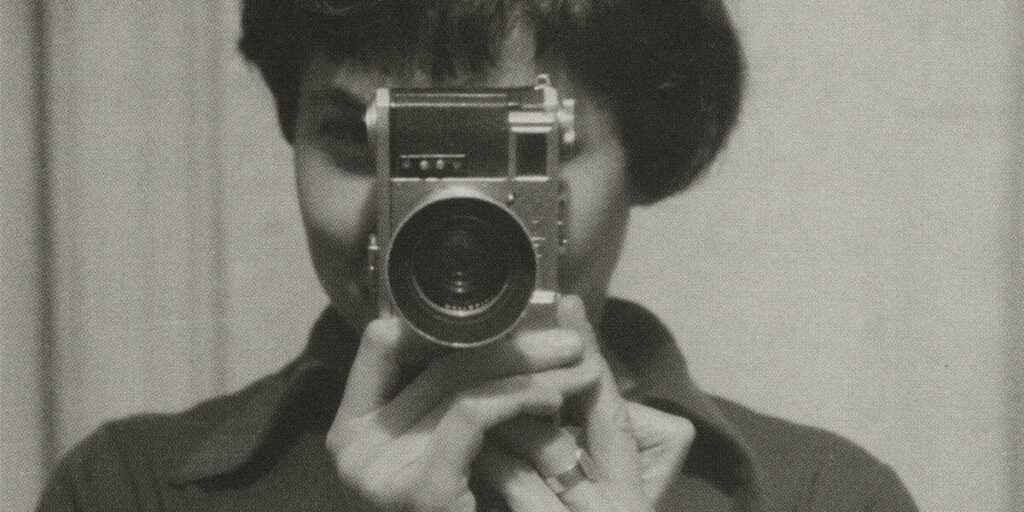

“To be a photojournalist takes experience, skill, endurance, energy, salesmanship, organization, wheedling, climbing, gatecrashing, etc. – plus, an eye and patience”.

These are the words used by the American photo reporter and filmmaker Ruth Orkin to define her job, printed almost like an epigraph on the falls of the Civic Museums in Bassano: this sentence summarizes and accounts for every single one of the elements that has played a role in her career as a photographer, just as the current exhibition running through the rooms of the museum manages to. Organized in collaboration with diChroma photography for the centenary of the birth of Orkin, it represents the first Italian retrospective entirely dedicated to her figure and is the only stop of a European tour, which is scheduled to move forward to San Sebastian (Spain) and Cascais (Portugal)

A remarkable event for the world of photography, proudly announced by Barbara Guidi, the new director of the Civic Museums of Bassano «I am very pleased to present the work of this leader of the twentieth-century photography. Her ability to merge together, in a perfect and mysterious alchemy, the captivating energy of the narration and the freshness of the moment, captured in a heartbeat, makes her of the most fascinating artists of the last century».

The exhibition moves across two vast rooms retracing and celebrating all the stages of the photographer’s career: one hundred and twenty of her most famous shots – from “VE-Day” to “Jimmy tells a story” to “American Girl in Italy” to the portraits of Robert Capa, Marlon Brando and Woody Allen – testify to her talent in extrapolating from the stream of life moments that are fleeting just on the surface, carrying the ability of becoming iconic, of displaying its evocative power and of transforming them into the world of a story. Those of Orkin are not just portraits or landscapes, but actual stories, tales in which places and people intertwine, communicate and mirror each other.

It’s not by chance that the cinematic language occupies a central role in Orkin’s poetics: child of arte, Ruth grew up under her mother’s wing, Mary Ruby an interpreter in silent movies, in 1920s and 1930s Hollywood, the so-called golden years. For this reason, the cinema remains as an everlasting shadow in all her artistic production, constituted of the strengths of both arts: spontaneity and theatricality, moment and narration. Each one of the frames is thus able to narrate a story.

The dialogue between cinema and photograph is a fil rouge that follows her for all of her life. At ten years old she receives her first camera, a 39cents camera that represents, for the young Ruth, one of the two means to achieve her life project and her emancipation. The other one is a bicycle: in 1939, at seventeen years old, she rides to New York to visit the great World’s fair. With her camera, she portraits people and places met in that lonely journey, and she makes them into a diary which is part of the exhibition.

Her need for freedom and independence reflects upon the way the represents her subjects: there is no intrusiveness, no pressure; on the contrary, you can feel her desire to just pass by, simply touching them with her eyes. This applies both to her travel journey and to the following work: people are photographed while they wait for their train, or sitting at a coffee table, deep into their thoughts. The photographer stands at safe distance, to respect and preserve those moments of intimate isolation. As she herself states in her autobiography, from which some abstracts can be read in the exhibition:

“I prefer it if my subjects don’t know I am there, or else are too busy to be aware of my presence. I would try very hard not to move unless it was absolutely necessary- and not to press the shutter unless there was some other noise to cover the sound- even though it meant I might lose a shot. The subject’s acceptance of me was more important. there could always be another shot. I called it blending in with the wallpaper”.

The people she seeks are immersed in their everyday life: ladies feeding stray cats, two girls playing, spinning one another around, a man selling watermelons: a poetry made of small thing, that wins the challenge of time and becomes a long-lasting footprint of life in its simplicity.

After studying journalism for a short period of time at the Los Angeles City College, hoping to work as a director for Metro Goldwin Mayer, Ruth, however, must face the sexist environment of the time. So, if on the one hand she finds herself forced to abandon her dream, on the other what she cannot do is abandon her calling, that for her is an intimate need: narrating the world. In order to do so, photography becomes the only path to walk, and in 1943 she moves to New York, where she works as a photographer in night club.

A passage from her autobiography tells us of her first steps, describing a modest and precarious situation, lacking the spaces and the instruments that she needed in order to do her work, in a small studio apartment on Horatio Street, which she shared with Jane Geitenby. Ruth writes of moving, in 1950, in a similar accommodation, a tiny and uncomfortable bed chamber in a two-room apartment on 53rd West Street: here she had to set the magnifier for her shots in the kitchen, at the cost of eating standing, like at a buffet.

These precarious conditions will soon be a memory: Orkin can boast a dazzling career, shooting for the main magazines of the time, become of the most important signatures in the field of photography

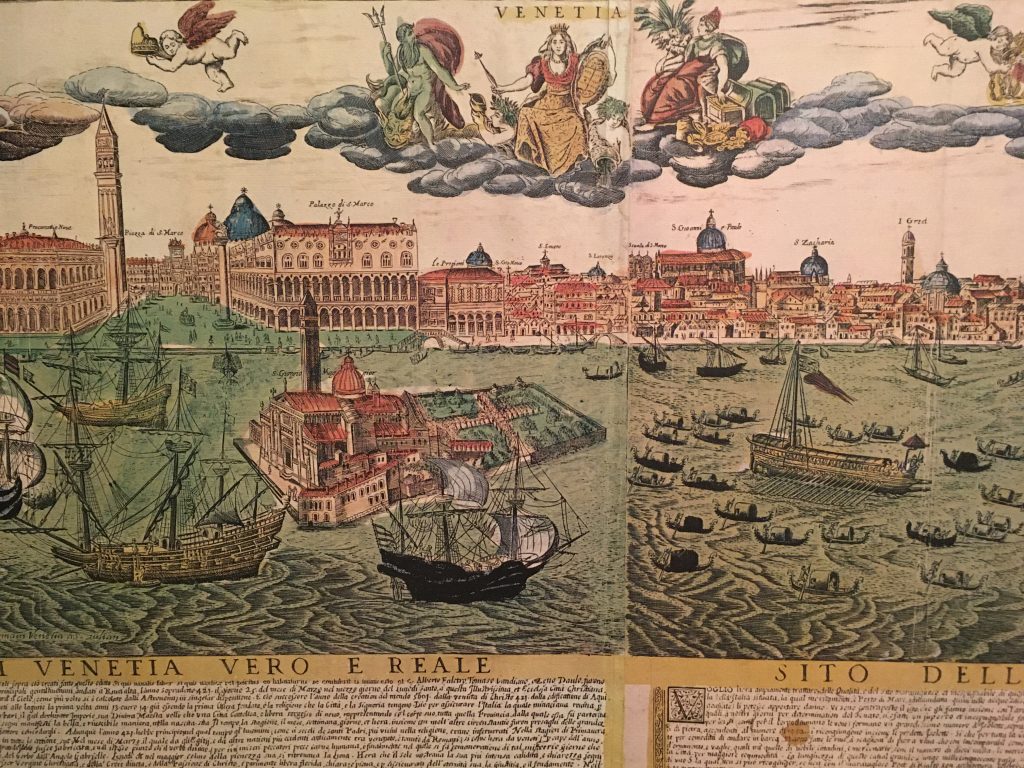

Alongside her works for LIFE, New York Times and other renowned newspapers, Orkin continues her personal journey in everyday life, birthing projects such as “A World Through My Window”, through which she narrates simply everything flowing under the windows of her apartment in Central Park (adopting an unusual point of view, from above, almost perpendicular: this demonstrates her knowledge of the German documentary photography of the Thirties, derived from the research of the Bauhaus, such as that of Otto Umbehr). In 1953 the dream of a lifetime becomes reality: with her husband, Morris Engel, and Ray Ashley, she directs Little Fugitive, winner of the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, which is also screened in the exhibition. Also what is considered a real icon of Nineteenth-century photography (and second most sold poster in the world), “American Girl in Italy” is accounted for in the rooms of the Museum: the photographic story of the experience of a young students in History of Arts, an American travelling in Italy during in the post-war period (in this case as well there are cinematic references: the frames recall the atmosphere of the American movies of the Fifties, starting from “Roman Holiday”). Orkin shows one more her ability to catch with her lens iconic situations, transforming them into the words of an engaging story, worthy of the best among directors.

“You can be a poet even without ever writing a poem, because for poetry made up of images, places, people, moments torn from eternity, all you need is a camera, talent and artistic sensitivity”.