Contemporaneity is progressively challenging many of its traditional and cultural aspects in the name of updating, modernizing. This is a natural process in any historical period and has to do with the progression of time, society and culture. But in the frenzy of our times, the debate – if it manages to take hold – involves only a narrow circle of people, while most are left with the bombshell, the headline on the front page, the caption of a post: this is because the debate is too long, time-consuming and media-consuming, and therefore counterproductive. It is true that even in the past, cultural reflection on the contemporary has always been the preserve of the elite, but today, in this very globalized world in which we have instant access to information, this should not be the case. The truth is that the constant barrage of flashes that is the avalanche of news we receive every day has disaccustomed us to a critical approach to reality, and we experience all its effects when, realizing that we feel lost, we despair and give ourselves away.

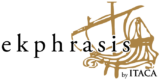

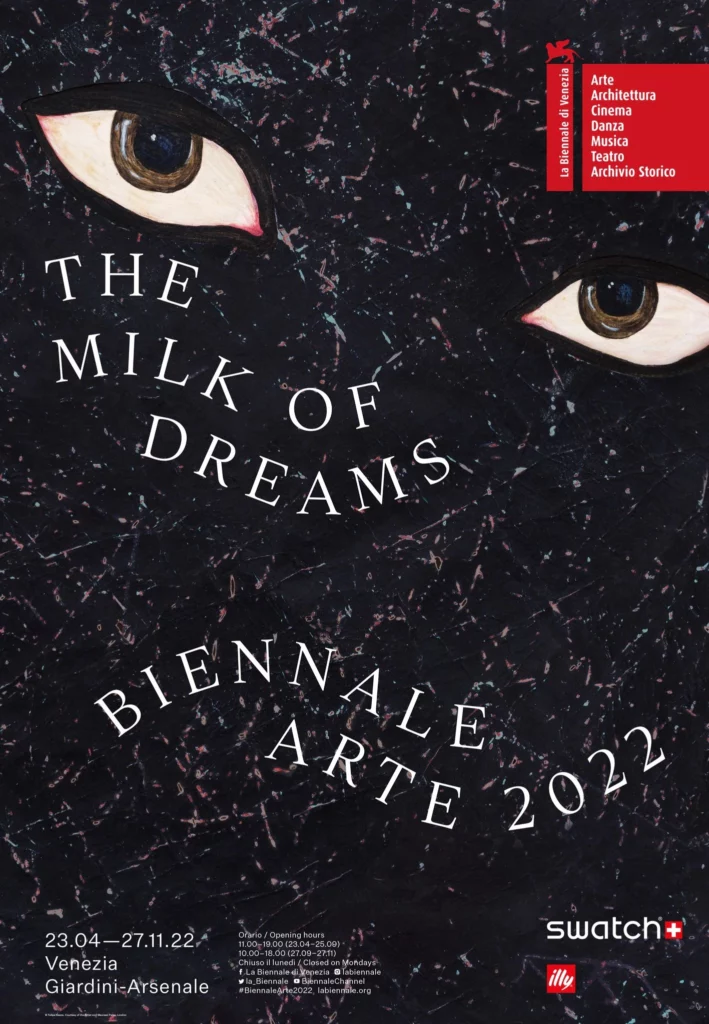

This edition of the Venice Biennale, curated by Cecilia Alemanni – the first woman in the history of the Venice Biennale – does not deal with a single theme, because our global present is multifaceted, it is plural, it is branched, it is satellite, and the purpose of this year’s exhibition is to present our contemporary in a timely and didactic way, trying to describe it as closely as possible to how it is perceived and dealt with in the different realities that make up the world (213 artists present). This is done not only in the different national pavilions present at the biennial’s Giardini or around the city, but also in the exhibition curated by the director, which runs between the Central Pavilion, Arsenale and Giardino delle Vergini.

This will be organized around 5 thematic capsules with a historical-didactic imprint, interconnected with each other, in which artists of the twentieth century who began to deal with themes such as the relationship with the environment, the recovery of folk traditions the redefinition of the human being in terms not only of his social role but also on a biological level – because of his very close interdependence today with the mechanical and the technological – are placed side by side with topical reflections by artists of our time to show how situations and approaches have evolved to come down to us, although often their beginnings, because they are far from the spotlight, are not yet part of “general culture.”

Starting from a common imagery, contemporary culture, the situations we are living in, and current issues-global and local-are waiting for us to take an organic path that is meant to make us think back, remember, rediscover, and above all, think.

To make people think, that is the social purpose of art. And the Biennials today have this role for society. Some will say no, “the Biennale is entrepreneurial, it was born in 1895 as an International Art Exhibition, where the bourgeoisie could spend their days in the halls of the current Central Pavilion and consider whether or not to buy works, it is heir to the culture of the Parisian Salon.”

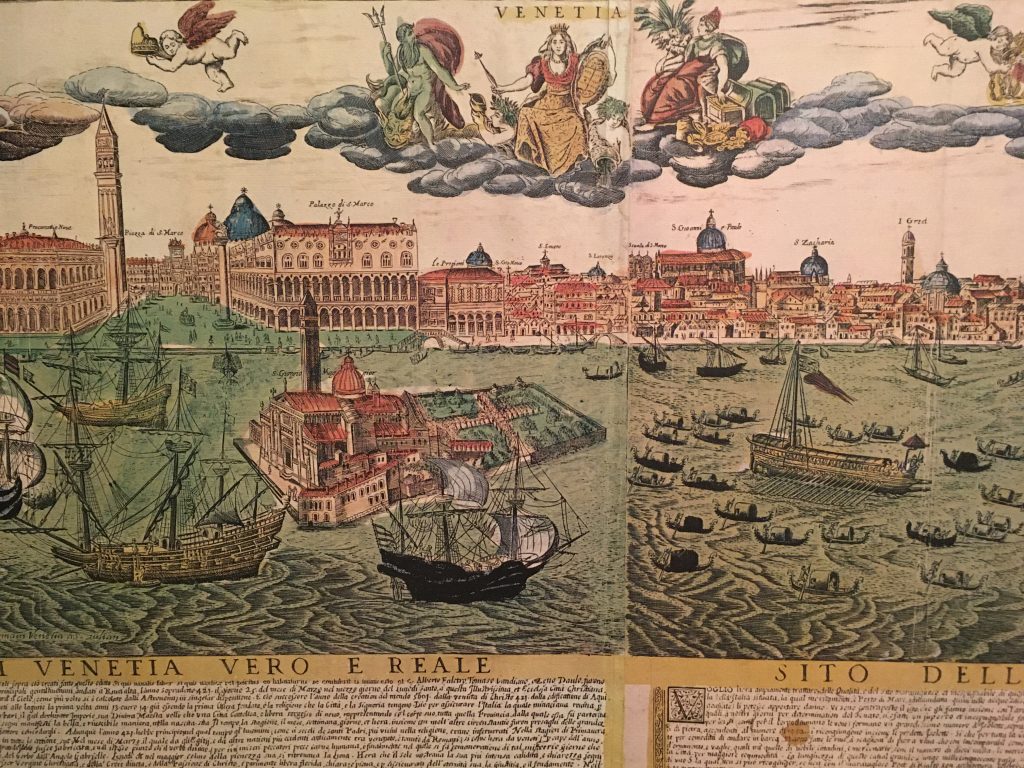

True, the Biennale is also that, it remains a key venue for contemporary art also from the point of view of visibility and success for an artist, but not only that: in its more than century-long history it has become an unmissable social event, this event has changed and has been able to reflect cultural changes, becoming the conduit for their dissemination to a wide audience, especially since the protests of the 1960s and 1970s, documented by Ugo Mulas’ photographs, which led the Biennale itself, progressively assailed by controversy and mutiny, to miss one edition, that of 1974. Before that year, the Biennale had only missed the two world wars. The fourth episode of “absence” was in 2020, due to the pandemic.

It seems appropriate to point out that a lot has happened in the last few months, starting with the outbreak of war in Ukraine: all of this will surely add new reflections and associations between the selected works and what we visitors will feel seeing them during our visit. The common thread that will guide us through this Biennial, starting with the title so eloquently affectionate, is a metaphor with childhood, with the recovery of a feeling of affection and love for the earth system of which we are a part and on which we should by now have realized that we are vitally dependent: it is the rediscovery of the power of imagination for the creation of alternatives.

Last year the title of the edition of the Architecture Biennale was “How Will We Live Together?”: already here we were presented with solutions, ideal and concrete, to the need to solve contemporary conflicts and problems concerning living together on this planet, but now it is the turn of artists, who have always been also somewhat magical figures, capable of making us think and above all dream. Milk was our first food: the title of this year”s edition invites us to be hungry – like babies at feeding time – because that hour has come, the hour or never again to become aware and take concrete action to turn our way of being around, really making a change in the monster way of life. The exhortation is to nurture ourselves as much as we can to come to understand what is going on around us, locally and globally, and become aware of it in a process of growth that will take us from being dreamy and hopeful children, to true active citizens, adults, able to think and act critically and consciously with a long-term perspective. We need to grow in our minds and hearts an awareness of the world, as every being needs to feed itself to survive and live in the world.

The figure of Leonora Carrington is taken as a reference for this year’s theme: a writer of fantastic tales and a surrealist painter who lived by rejecting the social conventions of her time, Carrington composed, beginning in the 1940s, tales about hybrid figures, often female, in which human and animal traits coexist, and toward which an ambiguous feeling emerges in the reader, one of repulsion but also of attraction: Indeed, in the inverted logic of the tale everything that initially seems absurd to us eventually acquires a meaning that, translated into our reality, ends up illuminating it.

So the ball is in our court, it is up to us to make a selection of the contents that the Biennial presents to us: each according to the person he or she is, for the culture and life he or she has, starting from the dreams he or she had when he or she was a child. All this starts from a return, a recovery of the consciousness of what came before us, toward which we should pose with enthusiasm and wonder just as we felt as children the moment someone told us a fairy tale, and not with a total contempt and rejection of what we have been. We have to do this with the awareness that sometimes fairy tales were also scary because they are ambiguous and invite us to unhinge our systems, with the knowledge that, however, everything always turned out for the best. We must do this because, as Rosy Braidotti states, “Despair is not a project. Affirmation, on the other hand, is.”