There are times when you realise that a date is not going as you would like. You can tell by the fact that you can see yourself in the third person, with coffee in your hand and death in your heart, while the ‘expert’ on duty says:

Yes in short, Pisanello – medallistics, frescoes, drawings… I’m telling you, no big deal.

Maybe you misunderstood. You hope so.

He is talking about Antonio di Puccio, that’s right, the refined painter and medallist of the first half of the 15th century; on his curriculum vitae appear the medals he created for prominent figures of his time, sacred works and frescoes, drawings, all scattered throughout his travels in the major Italian cities: a guest artist at the court of Aragon, at the service of lords such as the Gonzagas in Mantua, the Este, the Visconti and the Malatesta – he even had popes and emperors as clients, one name among all that of John VIII Paleologus.

A rock star. “No big deal”.

It has to be admitted that part of the annoyance is perhaps due to the fact that you are from Verona: the birthplace of the painter’s maternal side of the family, the city where he lived and where some of his best-known works are currently located, such as the Madonna of the Quail, the fresco of St. George and the Princess in the church of Santa Anastasia, or the Brenzoni monument. You think that maybe your suitor has never seen them, that he is ill-informed.

Because you know, I went to the exhibition in Mantua.

An intellectual. Something doesn’t add up.

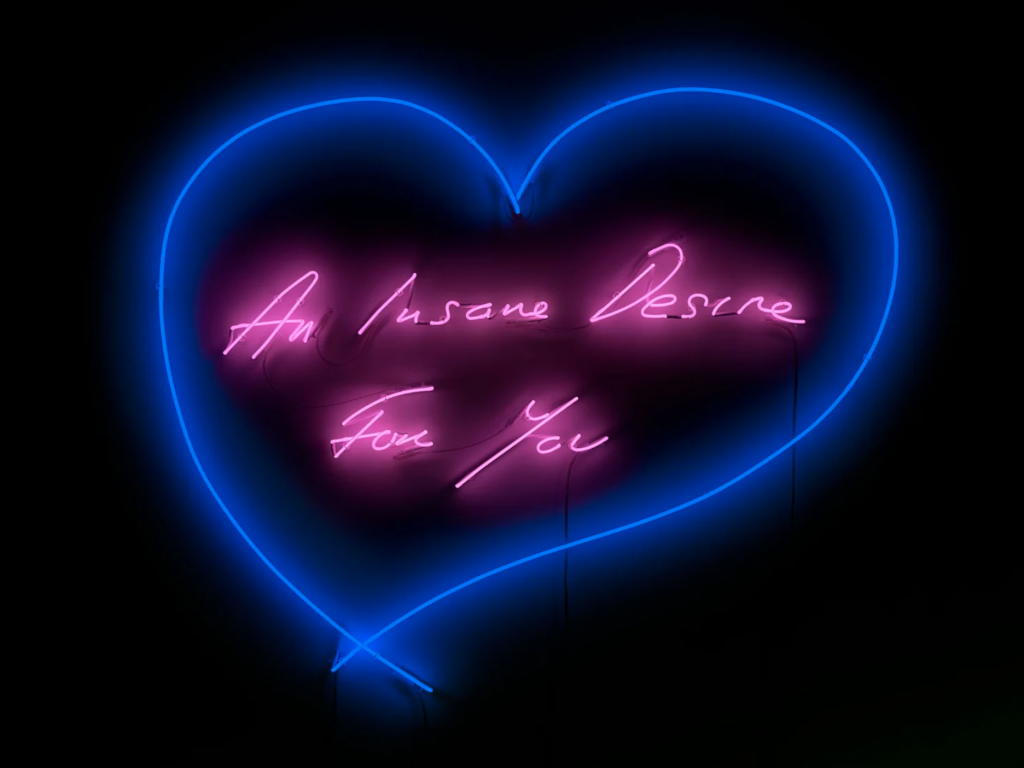

You know very well which exhibition it refers to, because you saw it yourself. In the last months of 2022, Palazzo Ducale hosted Pisanello. The turmoil of the world. 50 years have passed since Paccagnini’s exhibition, that is, 50 years since the first time the artist’s cycle of frescoes with a chivalric theme, until that moment hidden by later repainting, was exhibited – rediscovered after several centuries. The room in the palace had in fact been known until then as the Hall of the Dukes or Princes (due to the presence of a frieze with portraits of the Gonzaga family) and became the Pisanello Room, displaying the painter’s wall paintings and sinopias (the preparatory drawings).

On this occasion, however, 30 works – with loans from the Museo di Castelvecchio, the National Gallery and the Louvre – have been added to enrich the exhibition space: drawings, coins, paintings, panels; skilfully made choices that help the spectator trace the painter’s path of study, preparation and inspiration. Flamboyant headdresses and robes, profile drawings, animals, works of a sacred nature (the Madonna of the Quail is among the guests of honour; ‘the expert’ must have missed it).

Curated by L’Occaso, a permanent rearrangement of the hall was implemented: the real novelty. The lighting system and the raised platform – which places the viewer at the original distance from the work, as envisaged by the artist – clearly hint at the intention towards greater accessibility of the frescoes, coupled with a greater fairness towards the original intentions.

You think distractedly that if Palazzo Ducale were a starred restaurant, the exhibition would be the tasting menu.

And it is for this list of reasons that you fail to understand; what went wrong with him?

Let’s be honest. Drawing, yes, good; coins? Those work, too. But even on the walls does everything have to be so small? It’s confusing, you don’t really understand much.

Oh, that’s the point. It’s clearer now.

The ‘highly esteemed professor’ cannot be entirely blamed: after all, even the fresco of St George in Santa Anastasia is placed at a certain height. Nor is it difficult to understand his point of view, considering the fact that today, zoomingis always guaranteed and perhaps in some way demanded.

But then you think back to the interactive screen in the exhibition, which allows a clean view and access to the scenes that perhaps only Pisanello and the experts had – up until now – been possible, and one discovers details such as the incredible expressiveness of the men and ladies, the exertion of the horses engaged in the clash.

You also think, however, that part of the experience is also the seek: taking the time and curiosity to unearth the details and trace the stories, to let your gaze wander, as the Gonzagas also did at the time.

In fact, the characters open up a vast series of micro-stories: men of different ethnicities and cultures with their backs turned, on horseback, engaged in combat; on the ground, at the edge of the scene observing and discussing. Not only them, but also other elements add strength and depth to the narrative: their robes, the helmet lying abandoned by the knight, the broken spears and swords that can be traced in several places; a beast in the corner is tending its cubs, and this is just one of the much-appreciated details of Pisanello’s fauna and flora.

Pisanello seems to move skilfully in a courtly world with a fantastic, fable-like flavour, characterising it with a profound and extraordinary realism: characteristics that do not undermine each other but rather draw strength from each other.

The legendary princess of St. George dresses and styles her hair according to the trend of the time, her hairline set back according to custom. You can see the hats and faces and costumes of the gentlemen in the background in the frescoes of Mantua and Verona: so detailed that one can imagine the places and cultures they come from, the potential of the stories they carry. Fable and realism merge into a dynamic and deeply human plot: here it appears. The turmoil of the world.

Do you understand what I mean?

They say you have to pick your battles. They also say you should do sport three times a week, eat fruit five times a day and get eight hours of sleep.

You cannot have it all.

Get comfortable, I’ll explain.