Art goes beyond the limits in which time would like to compress it, and indicates the content of the future.

So says, within his own aesthetics essay Point, Line, Surface of 1926, the well-known artist Wassily Kandinsky; too well known for us to even consider proposing an original point of view on his figure. Starting from these words, however, it is possible to reason about what the future of art was in the following decades and how much the Russian artist influenced its evolution.

Exactly with this intention comes the exposition set up at the exhibition halls of the Candiani Cultural Center in Mestre, called Kandinsky and the Avant-Garde. Point, Line and Surface that can be visited until April 10, 2023.

The exhibition starts with some works by a mature Kandinsky, ten years after the founding of the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter, The Blue Rider (Munich, 1911), which included artists such as Paul Klee and Franz Marc, and following the period he spent in Russia at the outbreak of World War I.

Six of Kandinsky’s seven works in the exhibition are dated 1922, year when the painter returned to Germany and began teaching at the Bauhaus in Weimar and when his art reached the max height of abstractionism; indeed, the works clearly reflect the theories expressed by the artist on the evocative freedom of color and geometric forms that transcend the reality of sensory experience (The Spiritual of Art 1912 and Point, Line, Surface 1926).

This works are part of a portfolio titled Kleine Welten, Little Worlds, that consists of a total of 12 color and black-and-white graphics created by drawing on three different techniques: lithography, woodcut and drypoint etching. In it, the viewer can observe the depiction of a small cosmos of worlds, each one different from the other. Is this simply fantasy? The more observant viewer might notice that despite the extreme level of abstraction, it is sometimes possible to recognize certain architectural structures typical of the urban world.

It is only by connecting to the artist’s biography that one can understand the reason for these representations: in fact, in 1918 new urban planning projects had been approved in Russia, aimed at the redevelopment of Moscow as a “city of the future.” Small satellite cities would be planned around Moscow, capable of relieving the overpopulation and traffic congestion of the capital; Kleine Welten is therefore the outcome of a process of abstraction and internalization by the artist of certain historical and social facts contemporary to him.

The first part of the exhibition also presents some works by another artist whose biography and evolution was extremely linked to Kandinsky: Paul Klee.

Swiss painter contemporary with Kandinsky, he founded Die blaue Vier, The blue four with him in 1924, a group of artists who presented numerous exhibitions especially in America, and carried on the vision of the Der blaue Reiter group, of which he had previously been a member.

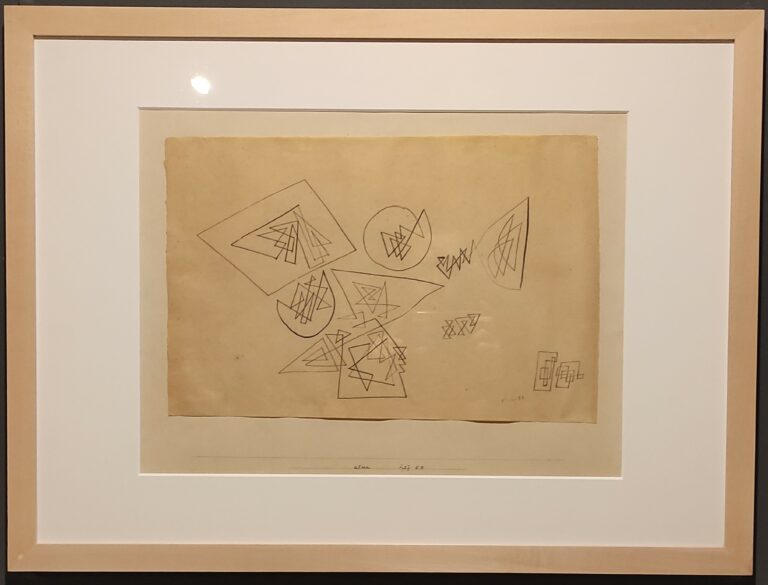

Displayed at the exhibition are several works that, even to an inexperienced viewer, allow one to grasp the influence the two artists had on each other. One example can be the work Alarm, displayed at the exhibition:

14 geometric figures, outlined by a single ink stroke, stand out on the paper. The starting point of each stroke corresponds to the end point of the figure, thus creating an infinite, repetitive circular movement. The very concept of line, for Kandinsky, corresponds “to the trace of the moving point, [to] the leap from the static to the dynamic” (Point, Line, Surface, 1926), to the impetus of external forces; moreover, broken lines are for him a clash of forces, a symbol of dynamism and tension.

Infinite repetition, dynamism and tension. At this point, remembering the deep connection in Kandinsky between music and painting, the title of this work may appear clear to the viewer: Alarm. The high-pitched, iterative sound and source of tension finds graphic expression here.

In the footsteps of Klee and Kandinsky, during the 1920s were born, as explicated within the exhibition poster, “the Surrealist experiments of Joan Miró, Antoni Tàpies, Yves Tanguy, the cosmic analogies of Enrico Prampolini, and the musical forms of Luigi Veronesi”.

Yves Tanguy’s work, Building and Destroying (1940) constitutes a perfect example of surrealism, which at first glance may seem very distant from the art of the two previous artists.

The amorphous objects and masses, placed in an unidentifiable and seemingly liquefied environment, the lack of elements clearly traceable to reality without any indication from the author: all this is strongly reminiscent of the process of abstraction of reality and input into the work of the artist’s subjectivity and emotionality present in the works of Kandinsky and Klee, although here the elements possess their own three-dimensionality and position in space.

Prampolini’s Cosmic Analogies (1931) also shows an abstract, barely recognizable female silhouette, in which, however, the Italian painter succeeds in sublimating the deeper essence of the subject, inserted into a colorful and mysterious cosmos. Colors and geometric shapes remain central, just as in Kandinsky, and do not refer directly to a trace of reality.

The next phase of the exhibition explores abstraction after World War II, presenting works by well-known artists such as Ben Nicholson, Giuseppe Santomaso, Mario Deluigi, and Emilio Vedova.

Here the different artists take very different paths, and interpret abstractionism in their own way. On the one hand, Santomaso; with the work that refers to his everyday life linked to the sea Wall and seaweed, the artist makes clear, as the synopsis of the work explicates, “his pictorial research thus lies between abstraction and figuration, oscillating between these two extremes without ever completely conceding to either”.

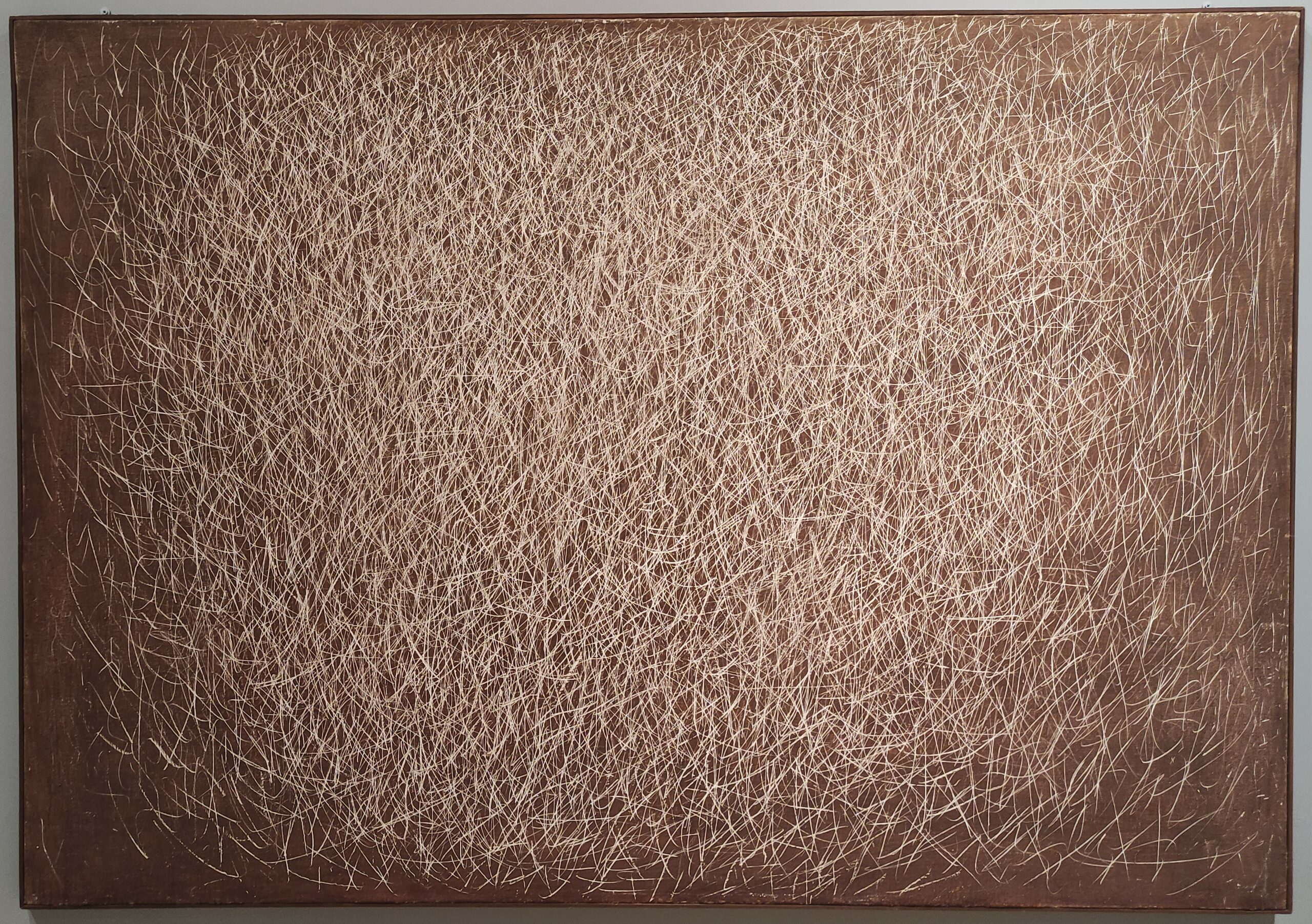

At the opposite apex is Mario Deluigi, who, using the pioneering mixed media technique of grattage, makes a study of signs and the balance that their thickening or distancing can generate, while abandoning any connection with the realistic signifier that may have inspired the work.

The exhibition concludes with a selection of sculptural works that verge on minimalism, in which Mirko Basaldella, Eduardo Chillida, Luciano Minguzzi and Bruno de Toffoli testify to the “persistence of the dialogue between abstraction and biomorphism towards the 1950s”, as it is said in the exhibition poster. Finally, a radical abstraction, at its most extreme, is represented by a pair of works from the 1970s by Richard Nonas and Julia Mangold.

What are they about?

I invite all readers to find out for themselves by visiting the exhibition. I can only conclude by writing that I agree with the statement of Kandinsky, an author who undoubtedly conditioned the art that followed him:

Art goes beyond the limits into which time would like to compress it, and indicates the content of the future.