A glimpse of life told through painting.

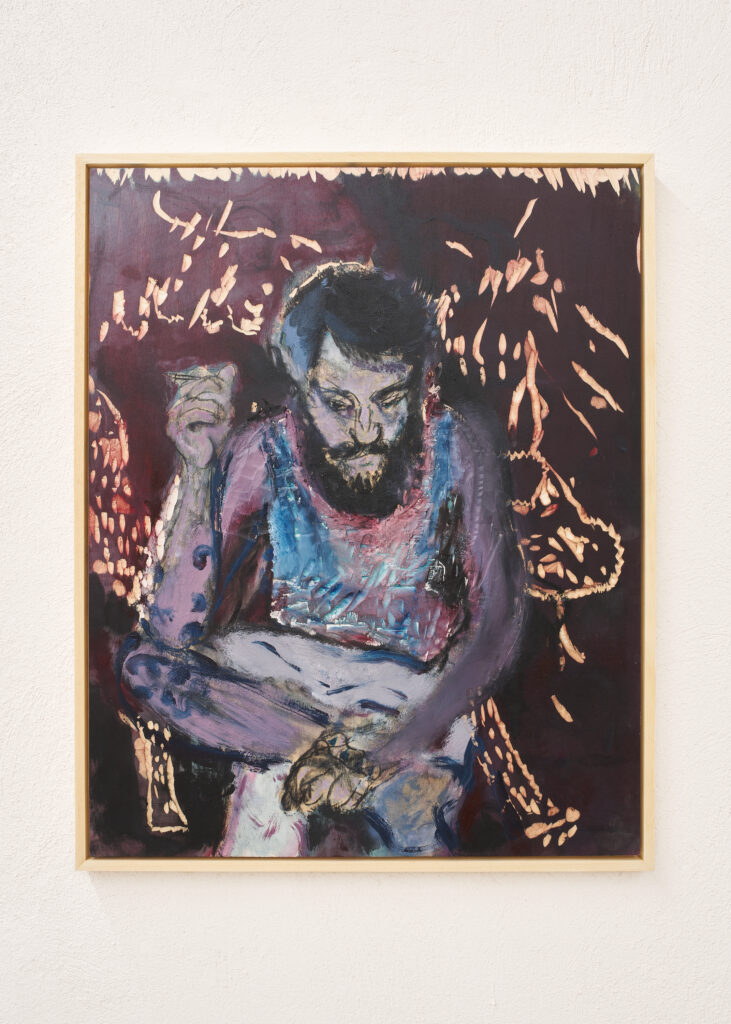

Fioi. In Venetian dialect: sons, brothers, companions, friends. In the art world: those who come to life in the latest series of works by Nebojša Despotović: The Famous Series of Fioi.

Entirely created in 2022 and the protagonist of the recently concluded exhibition at the Bologna gallery CAR (Nebojša Despotović, Another Race of Vibrations, 21/01/2023 – 04/03/2023), The Famous Series of Fioi, is a collection of memories and sensations linked to the artist’s private circle of friends and colleagues, the most intimate ones to the painter, who tells his story through them in a highly biographical and personal sequence of images.

Originally from Serbia (born in Belgrade in 1982), Nebojša, known as Nebo to his friends, moved to Venice early on, where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts and continues to work and live today (splitting his time between the lagoon city and Treviso), after a brief period in Berlin.

The people known in the Venetian artistic environment constitute the reference database for the 2022 series of works, marking a break in his artistic journey: for the first time, Despotović opens the doors directly to his personal experiences. The works are dominated by real scenarios, connected to the years spent in the surroundings of the Academy of Venice. Years of sharing, artistic and intellectual exchange, which the artist reflects upon with a sweet melancholy, linked to the awareness of time irreversibly passing and revealed by the works themselves, a layering of memories and emotions associated with them. Far from being mere documentation of reality, those told in The Famous Series of Fioi are complex mental constructions, non-linear narratives in which past and present merge and confuse.

The starting point is photographs taken by the artist and never completely forgotten over the years, which have had the opportunity to settle in Despotović’s mind, overlaying moods and references to the history of art over time. This operation is not at all new in his painting practice: Nebojša belongs to that generation of artists who fearlessly associate the great names and masterpieces of the past with today’s visual culture of photos, magazines, selfies, and social media. A common denominator in his production is the practice of drawing images from old photographs: faces and bodies usually anonymous, unearthed from archives, books, magazines at flea markets. Unrecognizable images, whose history disappears under dense brushstrokes, layered on top of each other.

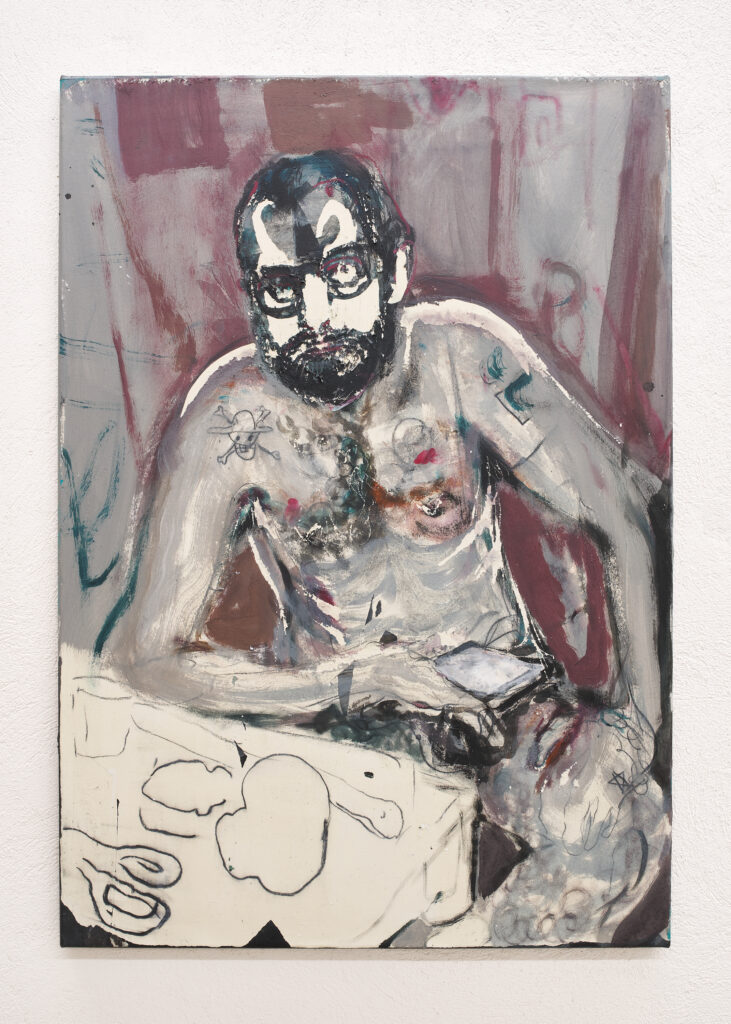

However, something changes significantly in The Famous Series of Fioi. The portrayed figures, whose names constitute the title of each work, are perfectly identifiable, each with their own physiognomy, attributes, and personality: Cima with the small One Piece tattoo on the right shoulder; Cri and his reserved soul; Nic with the thick mustache; Anna, with her expression so determined and strong, reminiscent of Frida Kahlo, and the prominently tattooed crucifix on her right leg. Moreover, the once dense and full brushstrokes now leave space for the support on which the images take shape: reasoning by subtraction, Nebo removes color to reveal the graphic aspect, the structure of the representation, too often hidden but now exposed in these works. For Nebojša, the sign is the most effective tool both for characterizing the characters and the artist portraying them. The graphic part, in fact, is what most tells of Despotović’s artistic practice, revealing all its vigor.

An emblem of this is the work Bach, where color is entirely absent: the white of the paper is marked only by the black traces of the artist’s gestures, revealing what has been (and is each time) the struggle between Despotović and the surface. For him, as Andrea Busto writes (in an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue Nebojša Despotović – The Golden Harp curated by Andrea Busto, MEF- Ettore Fico Museum, Turin 2020), “Painting is also a practice, it is a gymnastics and physical exercise, which takes place in front of the void of the blank canvas.” Despotović himself recounts how, before applying color, he trains daily with gestures and bodily movements (often listening to Bach’s music, as suggested by the title), which will only later translate into paintings. Bach, with its tangle of signs, so disordered, nervous, but at the same time controlled, capable of harmonizing the entire available space, tells of this bodily energy that fills the surface contained by the canvas, then spreading outside and involving the viewer

The reasoning by subtraction, combined with the physicality with which Despotović attacks the painting surface, is also found in Cima: here, the paper on which the color is spread is literally torn to reveal the underlying white; the color is thus removed from the face and the table in the lower half to better outline the narrative elements through the sign, allowing the scene to be contextualized.

The combination of corporeality and removal is also significant in Nic a Borca: the support is, in this case, a wooden board, where what may seem like lighter brushstrokes from a distance are realized, on closer inspection, to be portions of wood incised – or rather, scraped – deliberately coarsely with a gouge, a tool that allows for imprecisions, differences in levels, and vibrations.

What is extremely interesting in The Famous Series of Fioi is the great variety of supports, materials, and tools used in a single series of works: acrylic, tempera, ink, chalk dust, and glass dust, layered on top of each other, settling on paper, canvas, wood, making each work not only pictorial but tending towards an almost sculptural dimension. Works where cleanliness, precision, two-dimensionality readily give way to imperfections, paint clumps, unevenness, materiality. In particular, regarding the wooden works, the artist speaks of how they reveal his childhood in Serbia: the memory of his father, during the bombings of the 90s, recovering unused furniture from his grandmother’s house, working them with simple carpentry tools to make what could be useful to the family, has remained an indelible mark for Nebo, teaching him how with hands and creativity one can give new value to objects that are initially devoid of it, like canvas or wood.

What stratifies in Despotović’s works are not only different materials and brushstrokes but also temporalities. As mentioned earlier, memories of childhood overlap with those of the fioi, those belonging to his world, that of his present and recent past, as well as multiple references to the history of art. It is not a matter of citationism in any case, but of appropriation and reworking, where his personal style meets suggestions and reminiscences of Chagall (especially regarding the color palette), Picasso, Goya, Velázquez, Picabia, Munch, Tintoretto, Bacon, Morandi, El Greco, Tuymans, and all those artists who, beyond the form, also work on the painting surface in a gestural and material way. Despotović’s works thus become recordings on canvas, paper, and wood of traces left behind by his art history studies, memories of his more distant past, and of familiar, everyday images shared with people who are still part of his present.

Each mark, each brushstroke, therefore, is a sum, the result of all these temporalities, materials, and moods that the artist combines in his own exploration — a quest that is deeply personal. However, Despotović doesn’t confine himself to entering his own time and memory; he has the ability to communicate with that of the viewer. His works speak not only of the people and situations in the artist’s life, which we perceive as foreign to our own, but also of experiences that at times seem familiar to us, as if reflected in a foggy yet familiar mirror.

In doing so, he appears entirely contemporary: as Giorgio Agamben asserts, someone is contemporary who can transform their own time and “relate it to other times, reading its history in an unprecedented way.” (Giorgio Agamben, Che cos’è il contemporaneo?, Nottetempo, Roma, 2008) And all of us, in front of his works, are called to read our own history in an unprecedented manner.