Last year I spent a few months in Sweden, in Stockholm, where, while exploring the city and museums, I stumbled upon an exhibition at Magasin III that caught my attention. It was Revisit, a collection of past and new works by Mona Hatoum, a Lebanese artist who caught my eye because of the direct and incisive language of the installations on display and the fragments of video clips exhibited.

Hatoum’s artistic production, in fact, is often strongly influenced by her past experiences. In 1975, while she was in London, civil war broke out in Lebanon, which prevented her from returning home, forcing her into sudden involuntary exile and finding her to be stateless. Since then, she has lived between London and Berlin and has become one of the most prominent contemporary artists. In her career she has produced different kinds of works using multiple languages such as video, installation, sculpture, performance and photography, often dealing with themes related to home, memory, loss and making great use of the contrast between a sense of familiarity and alienation.

Indeed, in his contrasting compositions lies one of the most interesting communicative peculiarities of his works. Partly due to her experience of exile, Mona Hatoum deals with universally valid and extremely topical issues by questioning established truths and perceptions of the world: the perspective adopted is mainly that of the individual in relation to institutionalized structural violence and the exercise of power.

Due to the delicate situation we were experiencing and the tense climate caused by the difficult relations between the Scandinavian countries and Russia, talking about war suddenly became a contemporary and tangible theme in everyday life. This allowed Hatoum’s works to express themselves in a distinctly renewed and topical way, particularly attracting my attention when visiting the exhibition. Just a few days before my visit, in fact, some Russian planes had flown over the Swedish capital where I was and some air raid siren drills had been carried out to familiarize the population with the sound and instruct them on how to behave.

Some of the works on display had originated in 2009, when, in conjunction with the 53rd edition of La Biennale di Venezia, the exhibition Interior Landscape took place inside the spaces of Fondazione Querini Stampalia. The artist had been invited to confront the headquarters of the foundation by setting up and creating installations ex novo dialoguing with a place with a very strong personality. The result was an alienating effect in which the works on display bring the visitor out of the simple contemplation “at a distance” fully blending with the place and trying to reinterpret it by telling the artist’s past

This leads “Triumph of Beauty,” a ceramic centerpiece displayed in the foundation’s halls, to become the inspiration for Witness (2009), a work in which the Martyrs’ Monument in the Place des Martyres in Beirut is miniaturized and made into an ornament. From being a city landmark in a public square and an element charged with symbolic value, the sculpture becomes a simple object with a decorative purpose, ironically highlighting how the memory of the past can be too easily cast aside in a process of redefinition of place and reconstruction. The monument, moreover, has been scarred by the wounds of war for years, further charging it with an unintentionally significant symbolic value, and the artist also highlights in his scaled-down replica how the memory of the martyrs has itself been martyred once again.

Almost mockingly, then, Mona Hatoum finds herself talking about themes close to her heart by pointing out with oxymorons and contrasts the absurdities that arise, but in doing so she amplifies her message universally. It does indeed speak of being far from home and roots because of its experience, but nowadays it is much more common to feel a bit more nomadic and uprooted in a world where moving and relocating has become commonplace. Migration and instability are no longer big events, and being uprooted from one’s roots is something that young people are used to from early on.

Similarly, we can look at other works by the artist, such as the famous blow-ups of ordinary kitchen objects charged with a different meaning. In Grater Divider (2002), for example, we see how they become violent and awe-inspiring objects simply by changing scale and introducing themselves into the space in a contrasting and foreign way. They denounce the everydayness of routine and a society in which women still have to be bound to the home, but at the same time, by simply changing dimensions, they become new objects, all to be discovered and looked at as if for the first time. By adopting a surrealist gaze, we are no longer pervaded by the violence of blades, but we find ourselves having to understand the use of a new object, and in doing so we also speak of emancipation, feminism, and independence. The recognizability of the object allows us to see its more impetuous and animated side, but changing perspective allows us to distance ourselves again by assimilating new and profound concepts while bringing us out of the automatism of perception.

So we see how the choice of recognizable objects with a first common meaning for all is not unusual in Mona Hatoum’s artistic production, but the creation of contrasts and oxymorons is always loaded with a second level of interpretation that invites us to investigate deeply what we are looking at, fully involving us in the work.

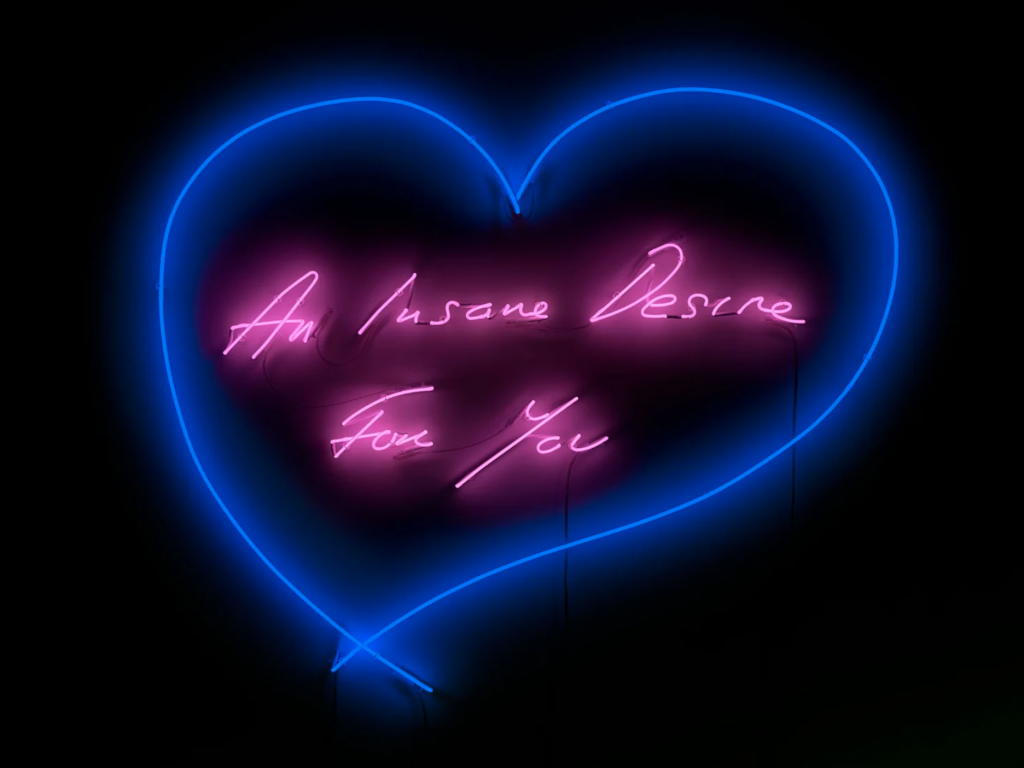

Looking at another of the works that originated in Venice but is also exhibited in Stockholm, we can see how the traumatic experience of war has been combined with the local culture of master glassmakers by inserting glass grenades inside one of the ancient glass cabinets in the room. Nature morte aux granate (2008) in fact softens through color and material those which are actually instruments of death used in the artist’s homeland. It gives them an extraneous fragility through the precariousness of the glass and a vibrancy of color that makes the grenades decorative objects similar to the fake fruit of still lifes used to adorn palaces.

It is interesting to note that this same communicative device of using an object symbolizing hostility softened and lowered into everyday life was used a few weeks ago by Banksy as a condemnation of the atrocities carried out in Ukraine. Among the various graffiti claimed by the anonymous street artist, in fact, we find one that depicts two children enjoying themselves on a Frisian Horse (an anti-tank barrier used to slow the enemy advance) as if it were a swing. As Hatoum recalls Lebanon, the British artist uses a war tool by decontextualizing it and entrusting it to the innocence of childhood to create a sign of hope that we can return to the squares to play and not to fight.

La Hatoum, dunque, parla spesso di conflitti e scontri, talvolta, come appena visto, cercando di esorcizzarli, mentre altre volte sottolineando la distruzione e il dolore impressi nel territorio colpito. La serie di sculture Bourj, infatti, è costituita da parallelepipedi realizzati con tubi rettangolari in acciaio saldati tra loro a formare uno scheletro simile alla struttura di un edificio a torre. Bourj significa proprio torre in arabo, ma gli elementi che compongono queste opere sono stati tagliati e bruciati, l’aspetto finale è quindi quello di un edificio segnato dalla guerra.

La denuncia verso i danni e la desolazione provocati dal conflitto è inequivocabile, e ancora una volta la scala aggiunge un ulteriore elemento di riflessione. Le torri sembrano infatti essere non delle riproduzioni, quanto piuttosto dei modellini progettuali pensati per il futuro, quasi ad affermare beffardamente come si stia già pensando ad un futuro in costruzione in cui sono già presenti i segni e le ferite della distruzione.

Queste immagini sono purtroppo tristemente note anche a noi oggi. Mona Hatoum parlava di una guerra per noi lontana nel tempo e nello spazio, ma ora che quotidianamente vediamo gli aggiornamenti di una situazione così simile da spaventarci, non possiamo fare altro che constatare come la devastazione e la fame di morte siano uguali ogni volta. Ancora una volta il messaggio di questa eloquente artista ci parla, senza volerlo, dell’attualità più estrema.