A young boy awaits us at the entrance to the exhibition.

From his balcony, which directly overlooks the Venetian lagoon visible in the background, the young man poses for the portrait painter with a proud gaze and finely crafted blue gowns, rich with gold embroidery and light lace, surrounded by precious leathers and red velvet curtains.

Next to the piece, these words:

“Welcome to our world. We will take you through the private rooms, where paintings will tell you about the tastes, desires and aspirations of our age. We will wander through patches of coastline, ancient ruins, whimsical inventions and sun-soaked fragments of the countryside, to land in enchanted territories where life is made of the same stuff that dreams are made of.”

The Shakespearean reference that concludes the last sentence perfectly introduces the visitor to the dreamlike and intangible atmosphere of the works that, after a few steps, he will be able to admire.

But who is that child? What are his origins? And his name?

The author himself does not reveal anything. But the role here, at the opening of the exhibition entitled In the Shadow of Canaletto. Landscapes and “whimsical inventions” of the Venetian 18th century, which will be exhibited in Padua at the Eremitani Museum until September 17, 2023, is evident: this child will become, throughout the exhibition, our young Virgil, who, holding our hands, will accompany us by land and sea showing us dreams, fantasies and wanderings of a bygone era.

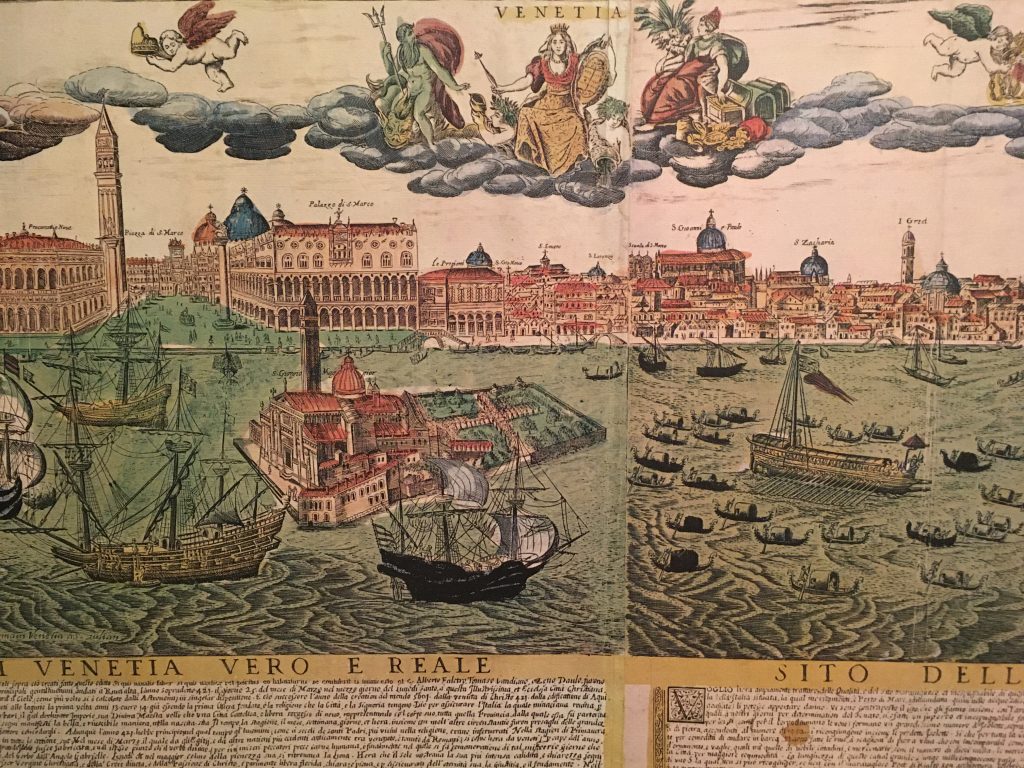

In particular, the exhibition focuses on Venice in the late 17th century. At the time, La Serenissima enjoyed a flourishing trade in Europe as much as in the East, and was home and studio to not only Italian but also foreign artists, who reached the peninsula to display their art and refine it, inspired by the great Italian artists who had preceded them.

The broadening of artistic horizons was reciprocal, however, as precisely from the 1700s two new pictorial genres, inspired by Nordic masters, were born and established in Venice: landscape and capriccio.

For many northern European artists (such as, for example, Johann Anton Eismann, who is present with more works in the exhibition) the landscape had in fact ceased to be a mere background on the canvas, becoming the real protagonist to whom to entrust the meaning of the work itself.

Thus, in the works of Italian artists the landscape advanced onto the proscenium in a big way. In an early season, Venetian artists not only depicted the Venetian countryside and the lagoon city, but depicted scenes in which Nature itself appeared particularly striking: maritime and coastal scenes in which the forces of winds and waters are unleashed on man; rocky landscapes surrounded by twisted logs and strong contrasts of light, as is evident in Antonio Marini’s work entitled Landscape with Natural Arch and Horsemen; and particularly harsh winters, visible in Francesco Aviani’s Winter Landscape with Adoration of Shepherds and Bartolomeo Pedon‘s Winter Landscape.

In these three works one can clearly see how much the natural environment, shown here in all its grandeur, is in the foreground. In Marini’s painting, the human figures occupy a limited portion within the canvas and are partly in shadow, while the sunlight seems to really want to highlight the huge rock wall behind, the stone arch and the two trees that, shaped by time, seem to twist together.

The other two works by the Venetian artists depict two harsh winters, capable of making human daily life more strenuous and harsh: we can see how the biblical scene of the adoration of shepherds occupies a liminal area of the work Winter Landscape with Adoration of Shepherds and that in the center of it is a white expanse of snow, which makes the distinction between natural landscape and dwellings complex and forces numerous shepherds to gather timber or protect their flocks inside the stables.

In Pedon’s painting, the viewer’s gaze cannot help but rest on the tree, which, with its icy branches, seems to want to hide behind it the traces of the port town depicted. Evidence of the harshness of the season, the frozen banks trapping ships, men hurriedly making their way to shelter, and a man who, below, seems to call for help after slipping on the icy surface.

As curator Federica Spadotto‘s notes along the exhibition’s itinerary state, “the pictorial capital of the 18th century did not stop turning its gaze to Northern Europe; indeed, it entertained a dense network of relationships with countries beyond the Alps. Its artists worked with satisfaction abroad, bringing back to the Lagoon the echoes of distant countries, seducing the public with tavern scenes, hunting parties and literary suggestions.”

Let us then look at Macbeth and the Witches by Francesco Zuccarelli; the scene clearly depicts one of the opening moments of Act I of the play, in which Macbeth and Banco (the two characters in the center) run into the Fatal Sisters as they are returning to their castles after defeating numerous armies. Here, the three witches will reveal prophecies to the two men concerning their fate and that of their future lineage; to depict this moment, Zuccarelli plunges the characters into a restless nature that seems to explode, to lose its mind. A strong wind shapes trees and shrubs; lightning strikes the castle in the background; river water bursts out of its banks, forcing a shepherd to flee with his cattle. The landscape is thus deeply involved in the scene and allows the viewer to feel the extraordinariness and grandeur of this moment within the narrative.

However, the depicted landscape was not always synonymous with uncontestable natural forces; from the 1730s onward, artists tried their hand at depicting bucolic and Arcadian places, in which, as the curatorial notes indicate, “graceful creatures disguised as humble peasants, embodying the ideal of beauty declined to joie de vivre” were at peace with each other and with the surrounding nature.

An excellent example present at the exhibition may be the work by Giovan Battista Cimaroli, entitled Landscape conceived along the Brenta with peasants at rest, in which the subjects are immersed in a dreamy atmosphere, with dawn light softly illuminating the treetops and reflecting in the river’s body of water. Observing the scene, the only rapid movement one can imagine is that of the dog who, at the bottom of the painting, plays with a stick together with his young master.

Let us now turn to the second pictorial genre that became established in Venice during the century: the capriccio.

In it, the curator states in a note, «the artist’s imagination garnished a rural or suburban setting of classical ruins, coexisting with the buildings of the time and sometimes with buildings of pure invention. Within these scenarios the audience was called to live a dream, where known places could become parallel worlds to be traveled and rediscovered every day».

Invented places then, devoid of coherence or rationality, whose main purpose was to amaze and enchant.

Let us take a look at Caprice with Friars by Antonio Visentini: here, the two characters appear tiny when compared with the storm clouds to their right and the immense and richly ornamented palace that, to their left, looms over the mountainous landscape. Such a setting cannot be traced back to any really existing place and clearly appears as the combination of imposing architectural and landscape elements meant to fascinate the viewer.

This pictorial genre also witnessed, during the last decade of the 1700s, a tragic Venetian political transformation, namely the end of the Serenissima. The occupation by French troops, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, of the territory belonging to the Republic of Venice decreed its dissolution in 1797. Venetian artists were profoundly affected by this change, and through the Capriccio attempted to escape from the reality of their own territory and to construct, in their paintings, alternative places in which the lagoon city, almost mirage or vestige, appears with traces in the works.

Francesco Guardi and Francesco Tironi provide us with two beautiful examples, with their paintings entitled Imaginary View with Classical Ruins and the Column of San Marco and Capriccio with Ruins and the Island of San Giorgio.

The dreamy and grandiose atmosphere offered earlier turns here into something enigmatic and uncertain, as the ruined places and architecture no longer belong to great civilizations of the past, whose traces remind us of the grandeur and splendor the peninsula had over the centuries, but rather to contemporary Venice, which will soon fall into the hands of the French general.

Thus, the Basilica of San Giorgio with its broad facade and bell tower and the lion of St. Mark seem to endure as a warning and symbol of the resilience of this great lagoon people.

It was precisely to celebrate and rediscover these Venetian cultural roots that this exhibition, All’ombra di Canaletto. Landscapes and “whimsical inventions” of 18th-century Venice, which will be on display in Padua at the Eremitani Museum until September 17, 2023, and brings together as many as 82 paintings belonging to museums and private collections of more or less well-known authors, both Venetian and foreign, who similarly became fascinated by the mythical city on water.

As the author Guy de Maupassant himself stated almost a century later:

«When we arrive in this unusual city, we invariably contemplate it with prejudiced and rapt eyes, we look at it with our dreams».

Guy de Maupassant, Venice, 1885