- – Head comic: “And the script? Where is the script?”

- – The Father: “It’s inside of us sir, the drama it’s inside of us, it is us”.

From the third act of Six characters looking for an author.

The time is 1905 and the place is Belle Epoque’s Paris.

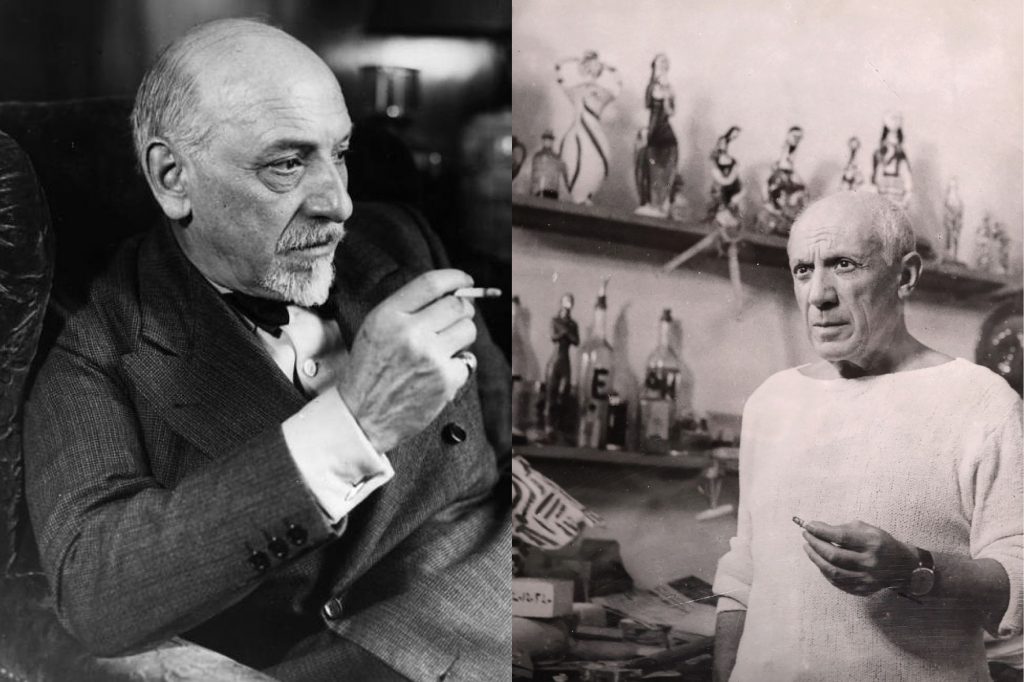

Against the backdrop of the Moulin Rouge’s glitz and glamour and a society which is still frozen in time in the 1800s, a young Spanish artist is busy painting the very same subjects that thirty years prior had been of great inspiration to another giant of modern art: Edgar Degas. Pablo Picasso couldn’t however be further from this artist that in his final years had so expertly portrayed the society of the Fin de siècle: if the first was a born Parisian, the second was only an adoptive one, having moved from Barcelona to his iconic and bohemian Montmartre residence of the Bateau Lavoir only in 1905.

That was a crucial year for the artist, as he was just then exiting a long period of mourning following the sudden and violent death of his friend Carlo Casagemas, event that had tinged his colour palette of shades of blue and had instigated in him a deep reflection about the meaning of his life and his art. Now, in the hope of reacquiring some of the serenity that had been robbed from him, and pacifying some of the doubts that the death of his friend had arisen in him, Pablo steps into a time during which, involved by his relationship with Fernande Olivier, he will try to be influenced by the colors and suggestive subjects of the Medrano Circus, a place located only a few steps away from his doorstep.

It’s the beginning of Picasso’s “pink period” during which, unlike the earlier one, his style of painting will now be characterized by a human warmth and a liveliness that had been severely lacking before: insert Family of saltimbaques. Often pointed to in art history manuals as the exemplary work of this time, it is in reality its most enigmatic: while the theme and tones used to render it are fully “on brand” for the time, the chiseled faces of the single figures, characterized by an indecipherable vacuous expression, are, in addition to an anticipation of the artist’s “African period” that was to come, the real centre of the composition: those lost eyes and hinted smirks that clash with the buttery atmosphere of the composition are indeed the true reason behind the slight but deep unsettling of the observer.

The circus family appears to be restless, quiescent, alienated … as if it were on the verge of breaking the pictorial illusion of the canvas so as to interact directly with the public, scrutinizing it, judging it and maybe asking it to help them: it seems as if each figure, alone in their drama, it’s asking itself what is his/her role inside of the composition and of their reality; exactly then like Picasso in this phase of his life, caught in between economical uncertainties, and maybe even sentimental ones, they too are asking themselves who is their author. And what is their happy ending.

The theme of alienation and of the search of self inside of a society increasingly “theatre of the great metallurgical poetry” – as it was defined by F.T. Marinetti –, is indeed the cornerstone of 19th and 20th century literature: on the push of the social changes generated by the industrial revolution, many are those that feel to have lost their “halo”, their identity, which is the very concept which will help us unlock the understanding of this mysterious artwork.

Bearing in mind the enigmatic gazes of Picasso’s saltimbanques, we are now being transported to a warm roman evening, in the May of 1921, when, at the Valle Theatre, it debuted one of the first meta theatrical drama devised by the genius mind of Luigi Pirandello, among the 20th century most esteemed authors: Six characters looking for an author. However, after much critical anticipation, the evening turns out to be a disaster and many among the audience, halfway through the show, stand up to protest it shouting “nuthouse! Nuthouse!”.

Pirandello had dared too much, even for the outrageous Twenties, as these years in Italy were dominated by the austere atmosphere of the “Return to order” movement, rendering it a period phased by Fascism and cultural trends such as “Novecento Italiano”. Six characters in search of an author was against the tide of the moment proposing a plot that, breaking with centuries of solid theatrical tradition, grafted itself straight in the audience’s lives, in a manner that, by being voluntarily provocative, could render them simultaneously observers and participants in the scenic illusion. It in fact talked about what happens to the characters of a story when these are dramatically abandoned by their author and how these very same six characters, lost in their incompletion, appeal to the Head comic of a theatre troupe demanding their half written story to be finished; their role, their very identity of characters is at stake, as left to their own devices they appear to be figures stuck between reality and illusion, half men hanging by a thread, incomplete and unresolved. By using this concept as leverage, it was Pirandello’s intention to challenge his audience and scatter in their souls the seed of doubt about their very life: am I too a character looking for my author and my happy ending?

It won’t be the last time Pirandello will provoke the public in this way: on June 5th 1937 the curtain would fall on yet another meta theatrical drama called The mountain giants, curiously centered on yet another theatre troupe, “The company of Countess Ilse”, that meets a different group of actors, the “Scalognati” (from the name of the Villa housing them), considered to be the true grotesque and melancholic emblems of the halo loss in the contemporary world. We assist here to an overwhelming return of the theme of alienation, the trait d’union between Picasso and Pirandello. The “Scalognati” are indeed the example of what happens in the contemporary world to those that look for their author and their ending: they pay the prize, being marginalized by a society that has become too superficial and industrialized to still recognize the irreducible figure of the artist; the same Ilse, female protagonist of the drama, at the “end” of it admits to feeling scared of doing it and being her true self when invited to perform in front of the giants. If she did or didn’t is still up for debate: The mountain giants remains the only unconcluded work by Pirandello, perhaps so as to let us choose for ourselves its end. Did Ilse redeem herself? Did she find the courage to regain her “halo” and occupy her legitimate place in the world?

This is what is essentially concealed behind the vitreous eyes of Picasso’s characters. Traditionally interpreted like the emblems of the artist’s newfound serenity they are in fact the very symbols of a drama more alive than ever in his soul: it’s the drama of knowing he is a timeless character that no longer has a place in the world of the 1900s and that will have to fight for a legitimacy by the society around them. It’s the tragedy of the halo loss and, at the end of it, the same drama that lives within us when we fail to fulfill our true purpose.