What do we reap when looking at an artwork? Astonishment, involvement, emotion or perhaps the much talked about Stendhal syndrome. Tommaso Marangoni takes on the question in his volume Knowing how to look: how to gaze at an artwork, where he creates a true guide to the observation of paintings and suggests that what we obtain through this act is directly proportional to how we look at the artwork in front of our eyes. But what happens when the canvas is unable to impart us anything, does not give us any clues, any life signals, not even a small hint of authoriality? It is in this moment that becomes relevant a figure that, despite sounding little known, has allowed the art market to evolve becoming among the most lucrative in the world economy: the connoisseur.

Borrowed from the French language, the connoisseur can be defined, like Donald Thompson writes in his bestseller The 12 million dollars stuffed shark, “a bit broker, a bit arbitrary of taste, a bit tour guide, a bit shrink”, a character so interdisciplinary that cannot belong to any discipline at all. Sure enough not necessarily does he have to be an art history academic that is aware of its critical implications, like one might believe at first sight, as his profession consists in pinpointing the elements that the artist leaves on his own canvas and that might escape the common eye, as if he were impersonating Sherlock Holmes reconstructing a lead on a crime scene.

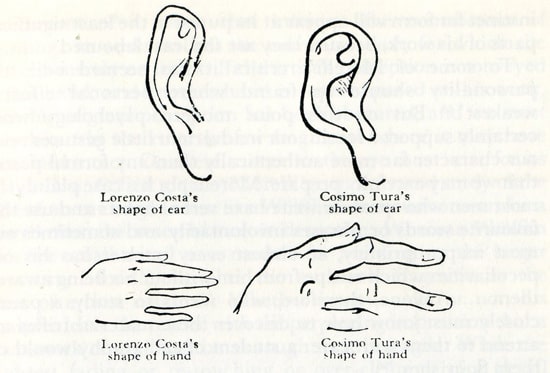

One of the first connoisseurs definable as such was Giovanni Morelli, who, during the first half of the nineteenth century, claimed in his essays about the Italian Renaissance that it was possible to identify the author of an artwork by the way certain anatomical elements were rendered in painting, like for example the fingers, the ears or even the gazes.

Perhaps unintentionally Morelli was giving life to a new way of observing art, of interpreting it and even of collecting it; it isn’t indeed accidental that we can trace back to this time the first major shifts of the international art market towards a new and previously unknown direction: that of the great American collecting. It is in this context, making himself into a fil rouge between the Old and the New Continent, that we insert a connoisseur that lived an era but seemed to have lived them all: the American-Lithuanian Bernard Berenson.

Harvard University was his mater studiorum, the old masters of the Italian Renaissance his wisdom oracles, Isabella Steward Gardner, one of the finest American collectors, his main sponsor, supporter and, eventually, client. Berenson observed art in a way no one had ever done before and if Morelli had unearthed the signature of artists in the mere anatomy of the paintings, the Lithuanian instead pushed through his discovery of their very soul: the tactile values, meaning the significances and logical connections deductible by the elements on the canvas’ or by the components that referred back to them (like symbols or the peculiarity of the stroke) and were strictly personal to the artist in question.

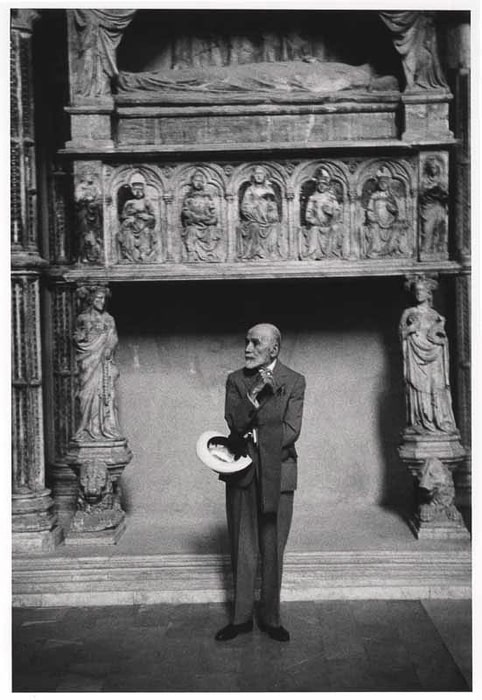

Berenson’s capabilities reinforced the character of the connoisseur to the point that he would come to be known as “the canvas whisperer”, or rather, that kept whispering and would keep on doing it so long as the human race was able to produce even a crumb of creativity. We can safely say that Berenson became the oracle of Nineteenth century collecting: with his attributions he shocked the art history world to its core, bewildering academics and non experts alike.

In between retracting the authenticity of a Titian and uncovering newfound Raphaels, Berenson realized that his words were starting to carry weight in his field and so the next step felt natural: transforming his talent into a source of income. Through this gesture, the role of the connoisseur morphed from passionate “art detective” into a masterpiece–hungry “Wall Street broker”. The geographical connotation of this last epithet is not again fortuitous: returning from his European and Italian adventures, Berenson often came back to the United States to foster his business deals with Mrs Gardner, almost to return the favor that she had granted him by single–handedly contributing to the scholarship that supported his first education in Europe.

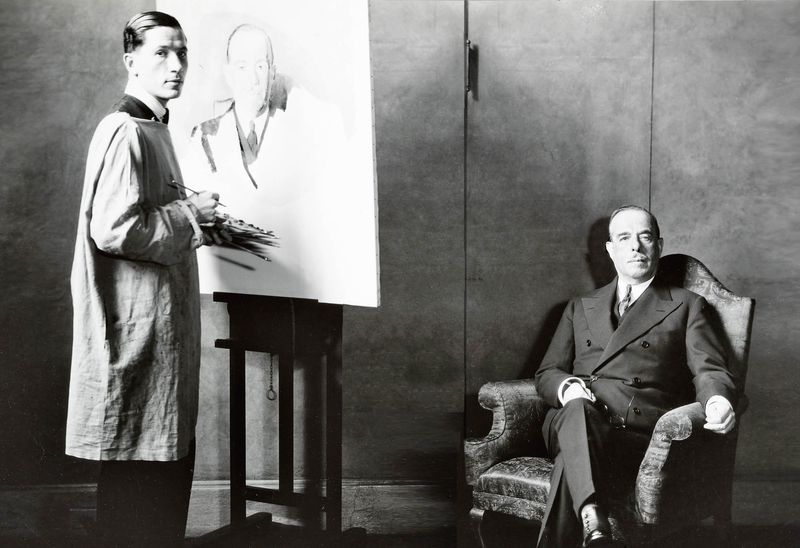

It was through Berenson then that the connoisseur turned into “advisor” and that the Continent changed, leaving way to the United States as the new land of art collecting in which the new God was strictly money. Differently than Berenson, whose inclination to sale had always been rocky, Joseph Duveen dominated this habitat: known as the “king of antique dealers”, even though he was not all that much, this man could have given up an Arcimboldo for a Caravaggio Still Life, and, because of this, he can be defined like the most forthcoming ancestor of the last evolving stage of the connoisseur figure: today’s auction house art expert.

True to form though Duveen had never wanted anything to do with auction houses and it was through a first education in the tapestry and antique ceramics business of his father Joel and his uncle Henry, the Duveen Brothers, that he fully learned the importance and direction of society’s taste, first British then American, in the art market, developing what would come to be known as the “Duveen eye”.

Through the New York headquarters of the business, Joseph had the opportunity to encounter major characters in the scene of the American art collecting observing their wants and needs and making sure to know exactly how to make them beg for something through the so called “shortage economy”, the fundamental tassel in the constitution of the Duveen method. Joseph was sure enough able to identify the taste of society without any regard at all for the artworks that he gazed at: any canvas that could potentially be sold had to be sold and the index that allowed the price to increase to ridiculous amounts was the collectors’ conviction of buying something unique, vivid and one-in-a-million.

Nowadays auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s, to cite two of the most renowned names in the industry, rest themselves almost entirely on the work of their specialist and their department chairmen who, as experts of specific time frames or object category, provide their clients with all the answers they might need so as to obtain as many offers as possible during the live auction and actuate a fidelity operation that will secure themselves as many future clients as possible.

Said process happens especially when dealing with contemporary art sales: being so seemingly complex to navigate and so volatile in meaning the clientele needs even more assurance when bringing to term their million-dollar purchase.

After all the core of the art market has been and will always be knowledge. The connoisseur is then the person that is aware of art’s and its present and future inhabitants’ secrets, having as primary goal that of always being one step ahead as compared to his contemporaries, to anticipate their every attribution and come to a checkmate in a handful of moves by wearing, depending on the occasion, the cloth of the art historian or that of the money hungry tycoon: a quick–change artist for every taste.