Palazzo Tes’ exhibition

Intrigues, murders, passionate loves, and vendettas.

Is it an episode of Desperate Housewives? No, it’s the art of the early 1500s with its constant references to classical mythology and the fables of Apuleius and Ovid; it’s an art that expresses itself freely, even in its eroticism, not yet stifled by the Catholic Counter-Reformation; it is, above all, the art of the frescoes by Giulio Romano at Palazzo Te, but it is also that of Peter Paul Rubens.

Although in the early 1600s the Counter-Reformation is still in progress, its restrictions are gradually loosening, and austerity is gradually giving way to the opulence of Baroque art. The imperial era of the papacy is inaugurated, where the fathers of the church, more than men of faith, are true aristocratic rulers, cultured collectors, and arbiters of taste.

It is in this context that the young Flemish artist is placed, who, without realizing it yet, will become one of the fathers of the Baroque.

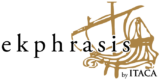

Just over twenty, Rubens embarks on a journey that takes him from Antwerp to Venice and then to Mantua. The young painter certainly fills his eyes with the vibrant colors of Tiziano and the grandeur of Veronese’s paintings, but it is above all his stay in Mantua, where he remains for 8 years, that is crucial to his formation. In particular, the frescoes of Giulio Romano, which Rubens had only seen through the black and white prints circulating throughout Europe, represent the reference point for his entire work. Imagine the painter’s emotion when he crosses the threshold of Palazzo Te and sees the frescoes live for the first time in all their spectacularity and vividness of colors.

It is from here that “Rubens a Palazzo Te. Pittura, trasformazione e libertà” starts, visitable in Mantua until January 7, 2024. The exhibition offers us the privilege of seeing Rubens’ paintings juxtaposed with the frescoes of Giulio Romano, allowing us to fully understand the interplay of references and connections. The magnificent frescoes of Palazzo Te were the perfect training ground for young Rubens, who managed to create a synthesis of the art that preceded him and an anticipation of the art that would follow.

Desperate Love

The exhibition, which cleverly juxtaposes paintings and frescoes, allows us to immerse ourselves in the adventurous and passionate stories they tell.

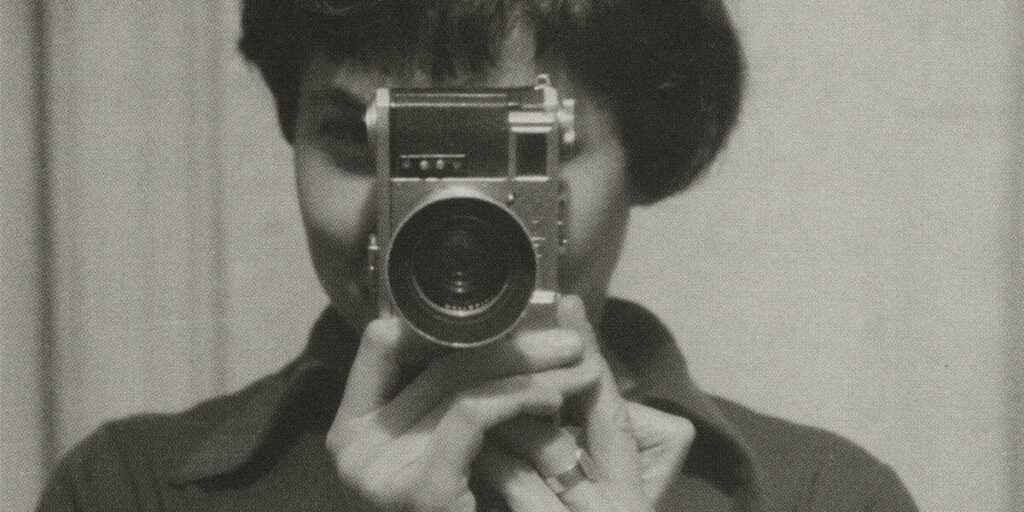

In the room of Cupid and Psyche, for example, the characters narrate stories of tormented love, envy, and revenge. Just as the curiosity of young Psyche by Giulio Romano is tempted by the envy of her sisters, who instigate her to discover the true identity of her lover, Rubens’s beautiful Deianira is tempted by fury. However, while the story of Psyche has a happy ending, Deianira is not equally fortunate.

Violating the pact of never discovering the lover’s identity, Psyche must face the four insidious challenges imposed by the goddess Venus as punishment. Despite Psyche being tempted several times to end her suffering through suicide, she manages to complete the challenges and can finally join in marriage with Love, entering the realm of the gods. Poor Deianira, on the other hand, falls victim to her own jealousy: persuaded that the robe soaked in the blood of Nessus has the power to make her forever loved by her husband Hercules, she makes him wear it, causing instead a gruesome death. Eaten by remorse, Deianira takes her own life.

The absolute protagonists of this room are the female bodies: elegant and statuesque those of Giulio Romano, voluptuous and sensual those of Rubens. However, the references between the two authors are not limited to mythology but also extend to stylistic exercises. We notice this in the delicate yet powerful body of Euphrosyne, one of Rubens’s three graces, whose contorted pose is reminiscent of Giulio’s Venus.

Hybris

In the eagle room, the theme of hubris, the challenge to power, returns, rendered so grandiosely in the room of the giants.

Phaeton, the son of Apollo, seems to fall right onto our heads. Blinded by pride and eager to prove that he is the son of a god, he takes the reins of his father’s chariot but, not knowing how to control the horses, meets a disastrous end. The young man, in fact, gets too close to the earth, setting it on fire. Zeus then hurls a lightning bolt at his chariot, causing it to crash.

Lucifer, in Rubens’s painting, meets the same fate: having dared to challenge the angels of God, he is defeated by a Saint Michael with shining armor and a vermilion red cloak, caught in the act of hurling a lightning bolt against the rebellious opponent, with the same power as the Zeus depicted by Giulio Romano.

Fallible Heroes

The works of Giulio Romano, like the ancient stories they inspire, are always dominated by a conflict, a strong tension between the characters and their emotions. This is particularly true for figures like Hercules or Achilles, heroes but not perfect, infallible. Both are driven to confront deeply human emotions, such as anger.

This humanity is well represented by Hercules’s hesitation at the crossroads, caught in the act of choosing whether to dedicate his life to vice or virtue, depicted by Giulio Romano in the frieze of the candlestick room; but also inRubens’s Achilles discovered by Ulysses, who, to try to escape the death he would face participating in the Trojan War, takes refuge at the court of Lycomedes, disguised as a woman.

The exhibition at Palazzo Te allows us to grasp a fundamental passage not only for Rubens’s formation but for the entire history of art: Rubens, able to draw from Mannerism and the classical references of Giulio Romano, the colors of Venetian painters, and Flemish attention to detail, comes to conceive a new international language, “a European figurative language, the first in the history of art”.

In this sense, the exhibition also becomes an opportunity to reflect on how there is never a complete break with the past, but rather a transformation that invites us to investigate elements of connection rather than separation.