“What you see is what you see”

Frank Stella

By focusing on the question in the title I tried to consider a series of thoughts I found myself dealing with on why such a specific artistic movement has been addressed by many with the labels of ‘Minimal Art’, or ‘ABC Art’, ‘Object Sculpture’, ‘Specific Objects’ and many more. Before starting, it is necessary to introduce, even in a few words, the academic description that has been given to this artistic movement, in order to reach a well-formed opinion on the subject matter.

Minimal Art has been, along with Pop Art, the most influential lifestyle of the 60s: it was, in fact, born from a common way of looking at things. Born in the USA, it had a major resonance in the artistic world and it included, among the artists, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt and many others. It was based on an extreme geometry of space and time, developed through artworks that share, as common aspects, the object as the subject, the strong formal simplification, the use of industrial materials, a cold-hearted and impersonal artistic language.

The expression “Minimal Art” comes from an essay by the British philosopher Richard Wollheim who, in the 1965 edition of Arts Magazine, referred to the works by the above-mentioned artists as having “minimal art content”. Although being simple representations of geometric shapes, mostly rectangular, these works of art are minimal only in their visual manifestation. In fact, the meaning that they hide is far beyond the mere “minimal art content” that at first sight they might convey. These new artists worked with substance rather than with concrete representation, but they distanced themselves highly from the Abstract Expressionist movement, declaring the central role of the object in its visual presence both in space and time. They focused on analyzing how a 3D sculpture modifies space and changes its perception depending on its position within the room.

Robert Morris, for instance, with his Column (1961) delved into the relationship between ‘space-object- observer’. Column was ‘worn’ by the artist during a performance at the Living Theatre and shown for 3 minutes and a half both vertically and horizontally. This apparently simple way of staging the act covered a deep reasoning: although during the performance Column only changed its position, this modified the way it was perceived by the public. It appeared thin and light when it was held vertically, while heavy and massive when horizontally inclined. Robert Morris (1931-2018) highlighted one of the main aspects of reality, one that is, in fact, simple, but most of the times forgotten by many: the multiplicity of things. How many times do we focus so much on one specific aspect of a situation and forget the remaining thousand ways of looking at it? How many times do we not see correctly, only black and white instead of rainbow? With Column, Morris wanted the public to stop for a second and see how a simple gesture in space, a change in position, a change in perception, influences all of the near surroundings, by modifying entirely how we simply see things.

One of the well-thought pioneers of Minimal Art, the artist Frank Stella, as reported in the subtitle of this article, once said “what you see is what you see”, which I like to interpret by changing the expression a bit: “what you see – in this specific moment – is what you see”: reality changes constantly, and what we see with our eyes is what reality is in that exact moment. Once we shift our perception the ‘thing’ mutates, and our eyes see a different side of it. But still, “what we see is what we see”.

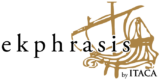

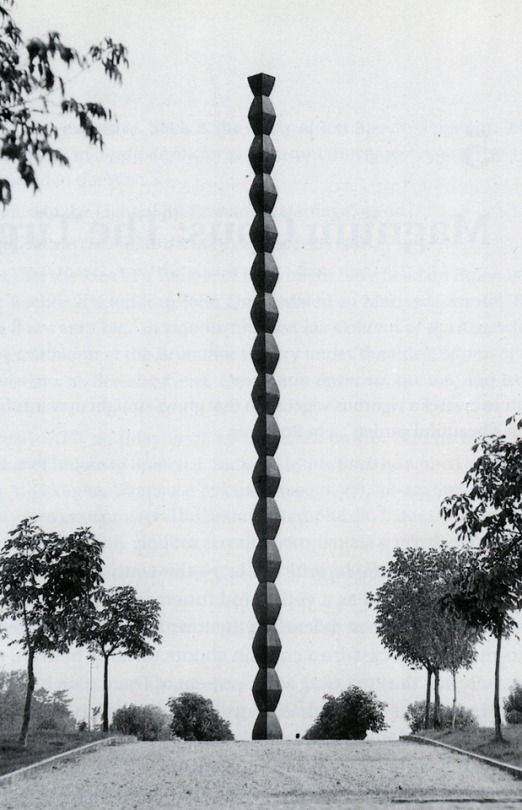

Another major name is that of Carl Andre (b.1935), an artist that has been strongly influenced by Brancusi’s work, in particular by Infinite Column (1938). In Lever (1966), Andre puts 137 industrial bricks in succession on the floor in a room on the occasion of the ‘Primary Structures’ exhibition. The site-specific sculpture changes the traditional understanding of a sculpture as such, commonly viewed as a vertical object and not a horizontal one. Lever changes dramatically the viewer’s perception, who could have either a finite or infinite understanding of it, depending on their point of view. From that moment on, Carl Andre created a series of ‘floor sculptures’ in various industrial materials and geometric shapes, providing a different sensorial experience depending on the components used. Sculpture was not anymore an object that evolved vertically but something that developed horizontally.

Minimal Art gifts us with artworks that we are not used to looking at. Minimal artists will not paint amazingly accurate landscapes, nor sculpt surprisingly real human bodies: they prefer to challenge the observer, so that they can question the meaning of what they find themselves in front of. Is it a column? Is it a rope? What do these bricks mean? The final answer does not matter, there is no unique explanation to one’s artwork. What matters is the effort of looking in a different way.

What made me question the reason why such art was called minimal is the true meaning that each one of these artworks retain. Something that is, once understood, far beyond minimalism. Although I understand that the pure visual representation of these 3D objects may lead to this definition – since they are not very detailed, nor painted with bright and various colors – I cannot help but wonder if this art is truly minimal. There is nothing minimal in the change of perspective, or in modifying one’s point of view. Through simplicity comes complexity, but calling Carl Andre’s works or Morris’ or Judd’s minimal is the same, to me, as choosing the ‘easy’ way instead of the ‘difficult’ one.