At the Maramotti Collection, the Venetian artist narrates stories of rebellion and dissidence through female gazes.

Gazes turned downward, heads bowed over sewing machines, young women composed and diligent in their white collars: a black-and-white photo immortalizes the perfect image of a women’s sewing school from the early 1940s. However, in this representation of order and diligence, there is an out-of-place element that disrupts the atmosphere of silent industriousness: a mocking gaze, in the second row, rises from the sewing machine, interrupting its own work. She is the Unproductive One, the one who gives the title to Giulia Andreani‘s exhibition at the Maramotti Collection and constitutes its icon and manifesto. For her first solo exhibition in Italy, the Venetian artist intends to delve into history, identifying and bringing to light a multitude of micro-stories: events and people who have remained invisible or fallen into oblivion, forgotten stories of rebellion and anarchy to which Andreani gives voice, connecting them with our contemporary society. Specifically, the period under consideration is between the 1940s and 1950s in Reggio Emilia, the years of World War II and the immediate post-war period: a twilight moment of struggle, revolt, resistance, particularly significant for the city hosting the exhibition and rich in echoes for anyone visiting. This historical moment is reinterpreted through a feminist prism, emphasized by the titles of the works, guardians of the artist’s statement, whose beginning is always a feminine article.

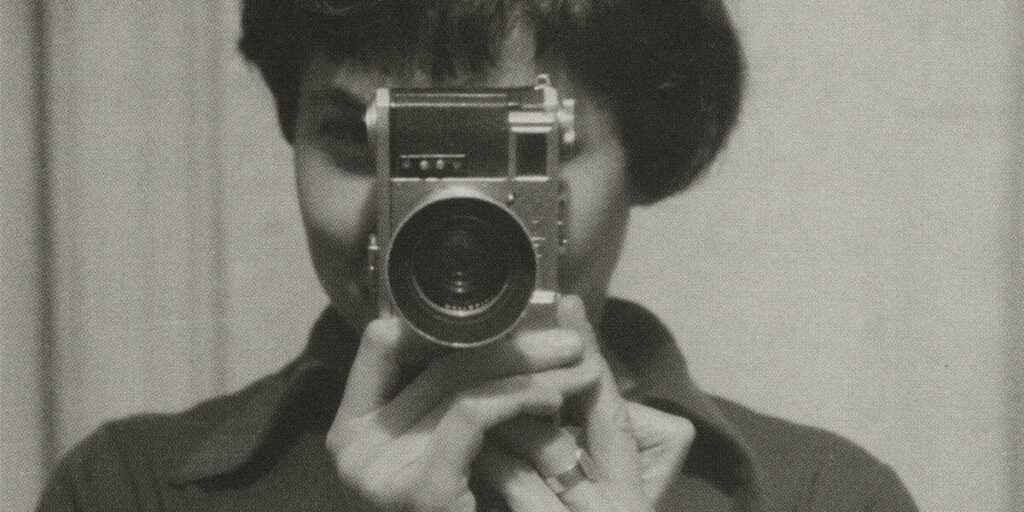

Painter and researcher.

The foundation of each painting consists of archival photos, among which Andreani – both a painter and a researcher – investigates and loses herself until she is struck by certain elements that completely absorb her attention. It is from these elements that she constructs the compositions of her works, the result of a well-defined idea of painting developed over the years.

Andreani studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and after graduating she moved to Paris, where she earned a degree in Contemporary Art History at the Sorbonne, temporarily abandoning brushes. Years of art historical studies then took her to Germany, where she pursued a PhD on the origins of painting in the Leipzig school, fascinated by the connection between politics and art. It is here, deepening her knowledge of painters from the German Democratic Republic, that Andreani finds the inspiration to resume painting, deeply struck by how they represented past history as a metaphor for the present. Another crucial input is the reading of Roland Barthes’ La Chambre claire through which Giulia deepens the concept of punctum, which becomes central to her poetics. The painting that Andreani decides to dedicate herself to is, therefore, a form of political painting that arises from archival research, starting from a photographic punctum that captures her and with which she cannot help but engage. The resulting painting is certainly a personal reworking of the original photo, but it remains faithfully linked to it, showing a deep respect for historiographical and archival research. The artist chooses a single color for her works: Payne’s gray, a dark gray tending towards blue, which leads the painting – and the viewer – back to a bygone era, that of black and white photos, emphasizing the historicity of the image; it is the shade of twilight, shadow, as well as memory and recollection. Furthermore, the use of a single color allows her to maintain a position of detachment, that of a researcher who is not distracted by the allure of color.

Women’s gazes

The works in the exhibition in Reggio Emilia are born from photographs preserved in three archives in the city: Istoreco (Institute for the History of Resistance and Contemporary Society), Panizzi Library, and the Archive of the former psychiatric hospital San Lazzaro. In each of them, the punctum that captured Andreani’s interest was the gazes of women: gazes like that of theUnproductive One,who, by lifting her head from the sewing machine, challenges the demand for productivity and also the male gaze of the photographer, hidden behind the camera lens and revealed by that mocking stare. A gaze that summons us, urging us to a personal rebellion: to be unproductive in the face of societal expectations, to resist the demands that oppress and compress us in our lives. Andreani is the first to respond to this invitation, questioning herself as a painter and the need to fulfill the demands of an increasingly pressing art system and market.

In the exhibition rooms, we also encounter the gaze of Nilde Iotti, a partisan and symbol of feminist movements in Reggio; Leda Rafanelli, an anarchist converted to Islam (and therefore dissident even within the anarchist movement); Maria Melato, an actress and proud single mother, portrayed with her son Luciano, unrecognized by her ex-partner but never hidden in her public appearances (a not at all obvious choice at the time). In La traghettatrice, the only work that combines different photographs, the mother-son pair coexists with the gaze of another young woman: a patient of the San Lazzaro Psychiatric Hospital, whose face fatally struck Giulia within the archive. In the original photo, the girl is captured tied to a chair, but her eyes do not surrender to the condition of captivity: Andreani decides to free her through painting, placing her on the bow of a boat, as if she were a figurehead.

The young figurehead is not the only one of the inmates at San Lazzaro present in the exhibition. In the next room, lined up side by side, are the gazes of seven other patients: anonymous faces that Andreani brings back from the shadows and arranges like an army surrounding and scrutinizing the viewer (thus reversing roles). This series of portraits is significantly titled Le sette sante attempting to restore to the monstruum (from Latin, that which is exceptional, exceeding the limits of normality) an almost sanctified value attributed to it by classical culture. The reflection related to these photos is extremely relevant: madness has been (and often remains) synonymous with marginality. The insane, the mentally ill, witches: these were the labels given to women who were simply different, exceeding social norms. What, then, do normality and abnormality mean? Who defines deviance, and how does this influence common thought? Who sets the boundary between sanity and madness? These are all questions that Andreani’s investigation brings to the surface through a constant attempt to celebrate marginality, a common thread that ties each of her works.

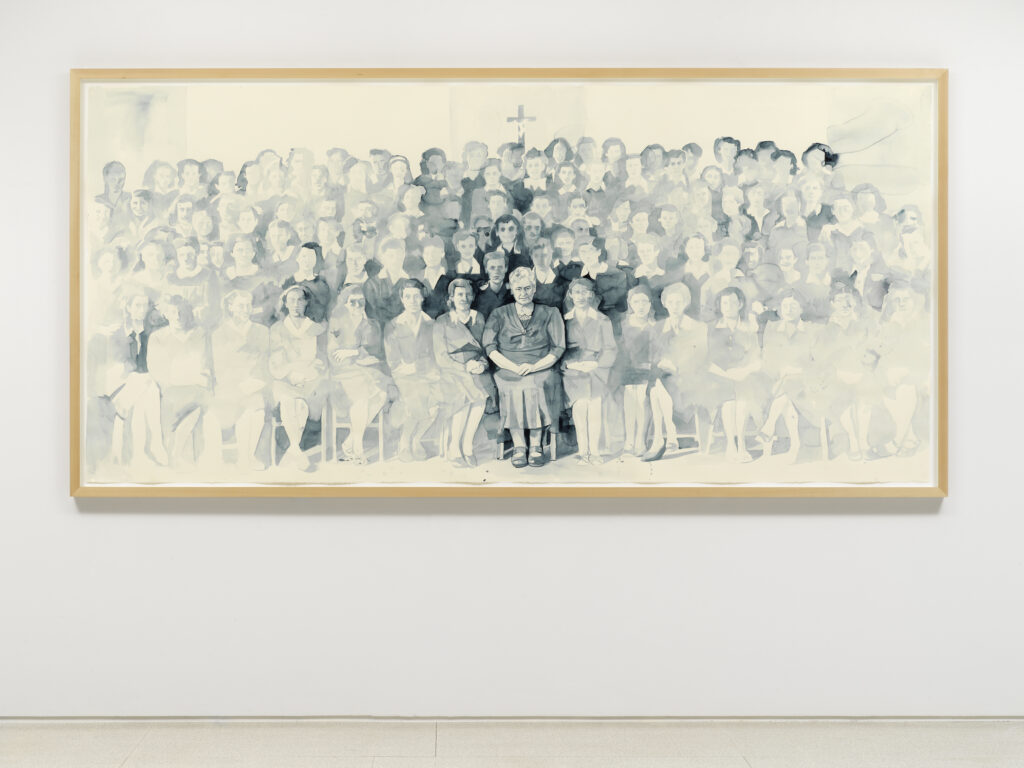

In the same room as Le sette sante, a second all-female army is represented by a group portrait of Giulia Maramotti’s sewing school. 114 figures are arranged in both a centripetal and centrifugal motion around the pivot (and punctum) of the composition: Giulia Maramotti, the mother of Max Mara’s founder (as well as the collector who gave life to the Collection that now hosts the exhibition). Maramotti’s face is the only defined one, summoning the viewer with a gaze that is firm, severe, and sweet at the same time, an expression of the “quiet strength” (as Andreani calls it) characterizing many women of those years, silent heroines and fighters. In this case, the strength of a woman who decides to open sewing courses so that other women could learn a trade for themselves.

The young girls around her, on the other hand, are progressively more undefined, with faces barely sketched, as if gradually emerging from the darkness. This indefiniteness breaks the rigor of the group (after all, it is still an institutional photo), blurs it, and makes it vibrant, giving the idea that the figures emerge on paper from the afterlife. Andreani plans to dedicate a painting to each of the young girls in the future, stating that from this single archival photo, a new exhibition could indeed emerge, confirming how each photograph contains enormous potential, a keeper of a multitude of stories. This one, specifically, was taken in ’42, in the midst of World War II: how will the lives of these women, mothers, daughters, sisters, have changed? Giulia gets lost in these questions, interrogates each of them. “It seems to me that I know each one of them. I have talked to them,” declares the artist. Giulia’s relationship with photography and painting is one of intimacy, of initial close contact, from which she then distances herself thanks to the use of Payne’s gray (a distance that allows her not to succumb to the pathos of identification, to remain rational and aware of what she wants to communicate).

The close contact with the painting intensifies when the technique used is watercolor: an extremely complex technique to master on large formats, but with which Andreani decides to challenge history painting as an academic genre. Traditionally executed in oil on canvas by men to celebrate great feats of great men, history painting is overturned and deconstructed by the Venetian artist, measuring herself on the same format but with a conceptually paradoxical technique: watercolor, the technique of “Sunday painting”, “for young ladies”, considered functional only for quick sketches and small landscapes. The use of watercolor for large paintings brings with it a series of difficulties: it is a fluid pigment that dries very quickly and leaves no room for touch-ups or regrets. That’s why Andreani works with the canvas laid on the ground, moving on it with her own body to avoid dripping paint, avoiding a possible painterly effect. A physical, contact work that leaves prints, accidents, which the artist decides to keep even in the finished work, as evidence of this strenuous physical struggle. So, in the bottom right corner of the painting La scuola di taglio e cucito you can clearly recognize Giulia’s hand: a mark that seems to belong to the same limbo in which the figures pass and becomes a manifesto of the artist’s practice: Andreani “gets her hands dirty,” digging into history.

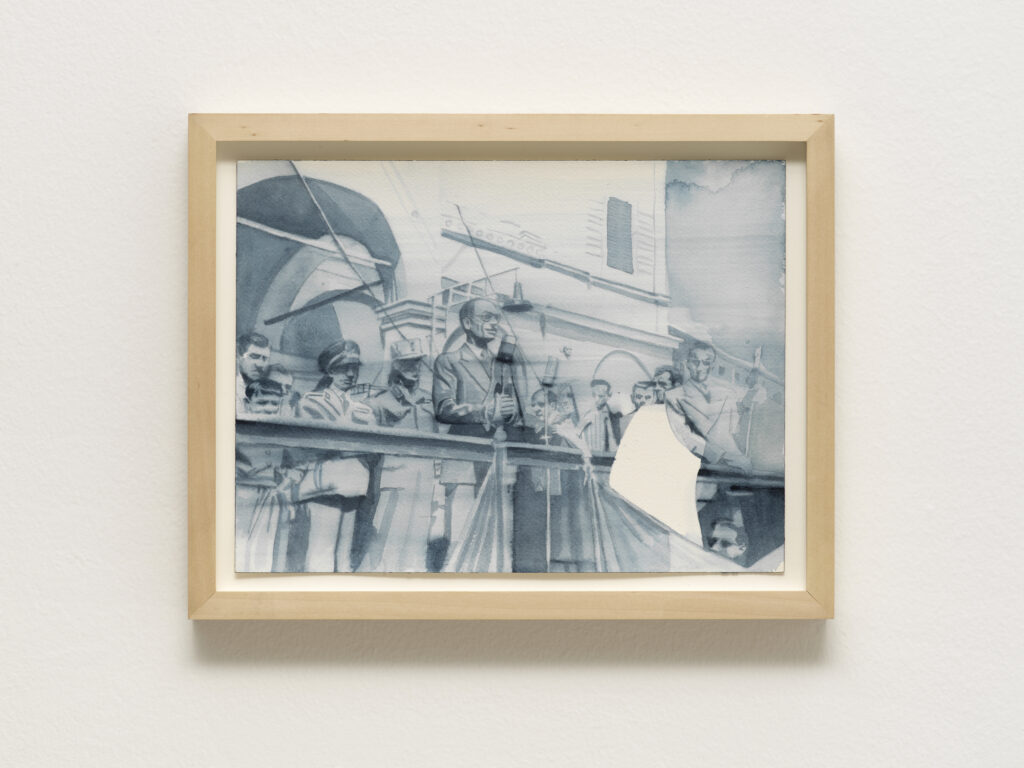

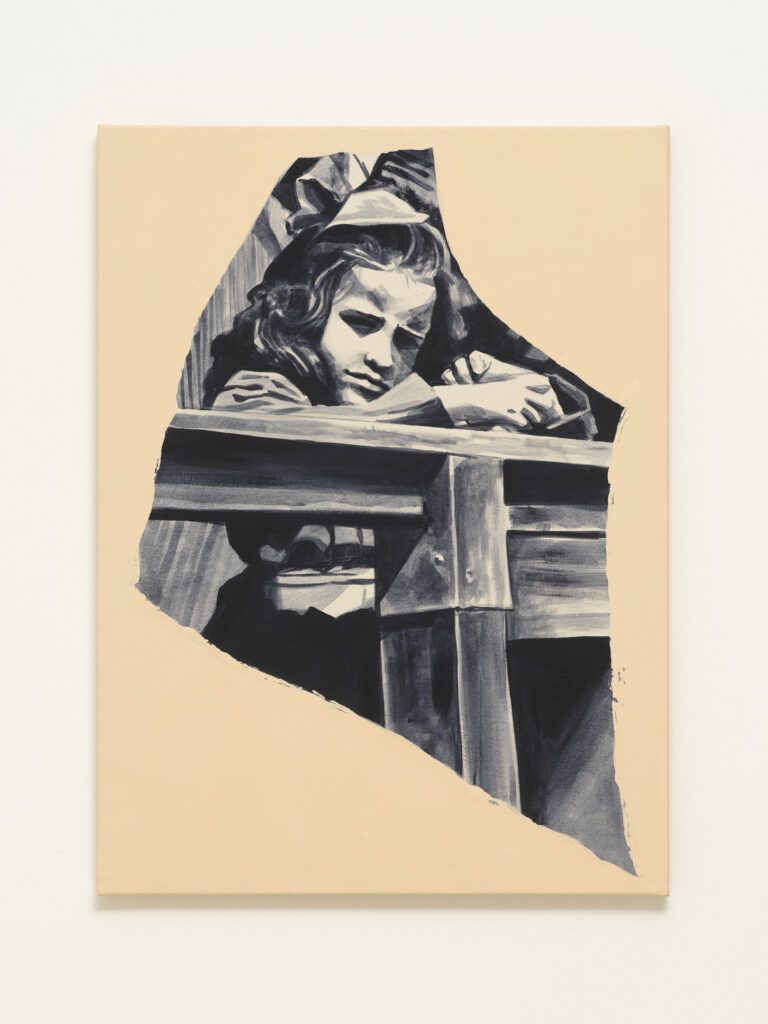

Giulia Andreani digs with her own hands into history and tears fragments from it, not so much to decontextualize them – on the contrary, historical context is always carefully considered – but rather to give space to the emancipatory force that those fragments already carry. One effective tear is the one made for the work La distratta: in a photo immortalizing a liberation party from the early ’50s, Andreani cuts out the figure of the girl on the podium, adorned and in ceremonial dress as required by institutional decorum, but with a bored expression and a distracted gaze, telling us that she, at that moment and in that formality, does not feel and does not want to belong.

Andreani puts two watercolors in dialogue: the first reproduces the archival photo but with a gap corresponding to the figure of the girl; the second is the enlargement of that “torn” face: an act of emancipation by subtraction from history and patriarchy. From a distracted (and passive) spectator, the young girl becomes an active presence within the exhibition, calling us, like all the other female gazes that populate the rooms of the Collection, to take a dissenting stance: to be Distracted, Unproductive, Anarchic, Free.