Background

Giuseppe Brion, a master electrician, founded his own consumer electronics company in 1945 in partnership with his wife Onorina Tomasin and engineer Pajetta. Initially dedicated to manufacturing components and radios, Brion quickly realized in the early 1950s that the emerging technology of the decade would be television. Thus, in 1953, with the acquisition of a new plant, he began producing TV sets. Brion soon understood that for his company to thrive among established electronics giants, it would need to stand out. To achieve this, he decided to focus on distinctive design for his products.

A Design Ahead of Its Time

It was in 1959 that Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper, two designers who had already successfully collaborated, were called upon. Their partnership with the company, which became Brionvega in 1960 after Pajetta left, propelled them into the top echelons of Italian and global design. At the time, almost everyone, including Brionvega, manufactured radios and televisions as wooden furniture pieces concealing the necessary electronic components, even featuring doors to camouflage their nature when not in use, blending them with other furniture.

It was time to propose something new. After a couple of models that achieved some commercial success despite not yet reaching their peak, in 1962 the deign duo hit the mark with a small television set that would become iconic: the Doney 14′. As the first portable and transistor television in Europe, it was a technical marvel too. In this product technology and progress were exalted by form and materials: a nearly perfect cube with rounded edges, its screen occupying an entire face. Thanks to clever component arrangement, its dimensions were dictated by the cathode-ray tube alone. The choice to echo the black color of the turned-off screen in the thin protective mask surrounding it was especially refined. Both contrasted with the rest of the casing, which was a vibrant solid color. In the first edition, the casing was even made of transparent acrylic, showcasing its internal construction. The controls were almost hidden, recessed into the casing along with the handle, preserving the overall purity of the form.

Clearly something had changed: the 1960s marked a new era. Newly invented plastic materials allowed for a variety of shapes and colors previously unattainable, in addition to excellent resistance and ease of production. It was the era of the space race, where technology was celebrated, while essential, functional forms, which were imagined to characterize the future, became desirable for home furnishings, offering a piece of that seemingly boundless future. Notably the designer duo, accompanied by Ennio Brion (son of the founder), paid a visit to NASA.

Zanuso and Sapper confirmed their prowess the following year (1963) with another project of even greater significance, winning the prestigious Compasso d’Oro industrial design award and being featured in several modern art museums, including the MOMA: the portable television Algol 11′. Almost a natural evolution of the Doney, it retained the color scheme and the general square shape with rounded edges, but introduced a bend to tilt the screen upwards, making viewing easier when the television was placed on a surface.

In the same year, the designer duo also created the portable radio TS502, better known as the Radio Cubo for its characteristic shape: two hinged cubes with a style similar to that of televisions in shape, color, handle, and concealable controls. The controls, scales, and actual operating circuits are housed together in one cube, while the other is occupied by the speaker This object, with its typical minimalist and cheerful style, is also displayed in several modern art museums.

In 1965, with the increasing popularity of home Hi-fi systems, the company decided to enter this market segment. Thus, from the design of the Castiglioni brothers, the radio-phonograph RR126 was born. Besides its clean and essential style, characterized by voids and solids, black and color, it stands out for two very modern features: a certain playfulness and modularity. It’s playful in its anthropomorphic appearance, where the scales form eyes and eyebrows, and its shapes invite interaction. In this sense, the object is not just a beautiful piece of decoration but something that encourages its use. RR126 is also a modular product, the speakers can be positioned differently: above the main body in a compact square, attached to the sides in the most classic arrangement that allows for good stereo separation, or simply wherever desired in the room, within the distance allowed by the cables. It was also one of David Bowie’s favorite stereo systems, who also owned a Radio Cubo.

Subsequently, the Sapper-Zanuso duo made their return to the Brionvega lineup in 1969 with the Black ST201 television, a perfect, glossy black cube with an inscrutable appearance: when not in use, it’s nearly impossible to tell which side constitutes the screen. Looking at it, it’s almost impossible not to think of another black monolith that had just entered the collective imagination the previous year, where it would remain: the Monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey Considering the non-immediate timescale of industrial product realization, it’s unlikely that the Black ST201 television was directly inspired by the film or intended as a reference. Still, it’s reasonable to believe that different creative minds, in different fields and with different experiences, could draw from the contemporary zeitgeist, arriving at similar results and interpreting similar suggestions .

Meanwhile, in 1968, Giuseppe Brion passed away, which had no consequences for the company, as it passed into the care of his widow Onorina and son Ennio. However, this leads us to the second chapter of our journey. In fact, the two wanted to honor Giuseppe’s memory with an appropriate tomb, and to do so, they turned to an architect who, according to their own words, “was also a poet.”

Carlo Scarpa and the Brion Monument/Tomb

Until then, Carlo Scarpa, despite having considerable freedom of action, had always been limited in his commissions: sometimes because he had to restore and integrate existing artifacts, such as in various museums and exhibitions he curated, and other times because they had to meet specific needs, such as in housing.

When the Brion family asked Scarpa to create the funerary monument, he had the opportunity to make extensive and unrestricted use of his expressiveness: it was granted to him by the clients precisely because of the poetical opinion they held of him. Thus, what was originally supposed to be a private chapel in the small cemetery of Altivole became only the entrance to a complex constructed by annexing adjacent lands to the cemetery on the north and east sides.

The monument is a stratification of layers and meanings, not centralized in a single entity but spread throughout the available area; each part has its role and enjoys expressive autonomy while interacting with others and maintaining overall coherence in a nonlinear path. Let’s start from the base, quite literally: one could almost overlook it, but the ground level within the monument is higher than that of the surrounding countryside and the rest of the cemetery. This recalls tumuli, the earliest human monumental burials, earth mounds that blend into the landscape.

The relationship with the surrounding landscape is significant; due to the height and inclination of the enclosing wall and the pierced angles, the monument area is not isolated from the external landscape but becomes a tranquil place from which to contemplate it. The wall itself shields from view the chaos of human daily life but allows the visitor to behold the extensive hilly countryside, the villages with their bell towers, and the Rocca di Asolo.

Turning our attention to the use of water features, a constant element in Scarpa’s work, practicly a reminder of his venetian origin. Water is used in various forms: from narrow channels running through the external area, reminiscent of Moorish gardens, to deep pools with water lilies and fish as in Zen gardens, Scarpa was indeed fascinated by Japanese culture, but water also appears in thin sheets acting as natural mirrors, like near the “Tempietto” with concrete mouldings beneath, almost simulating the foundations of ancient ruins. It’s worth noting that both in the terrestrial paradise of the Judeo-Christian tradition and in that of the Islamic conception, there are watercourses running through them; in this sense, the water-permeated garden becomes a direct reference to the afterlife, of which the Monument becomes a terrestrial representation.

The Japanese influence is evident in the meditation pavilion, characterized by absolute calm and abstraction, but it’s also found in the marble inlays of the interiors with squared white motifs defined by darker strips, akin to Japanese doors and walls made of rice paper, thus giving marble an additional lightness.

In an area excavated in the lawn lies the actual burial site: the sarcophagi of the two spouses, squared and protruding towards each other as if to touch, bear witness to a bond that continues beyond life. Exposed to the elements, to nature, they are at the same time sheltered by a low reinforced concrete arch with essential shapes and elegant moldings. This arch reveals its full beauty only to those who, passing underneath it, gaze up at its brilliant glass tesserae, reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics. Scarpa himself referred to himself as “Byzantine” in interviews; indeed, although a thoroughly modern architect, he retains memories of the ancient cultural references in which he was raised. This large arch continues the historical reworking of mourning by recalling the arcosolium, the ancient burial typical of catacombs, where the bodies were placed in an arched niche in the wall.

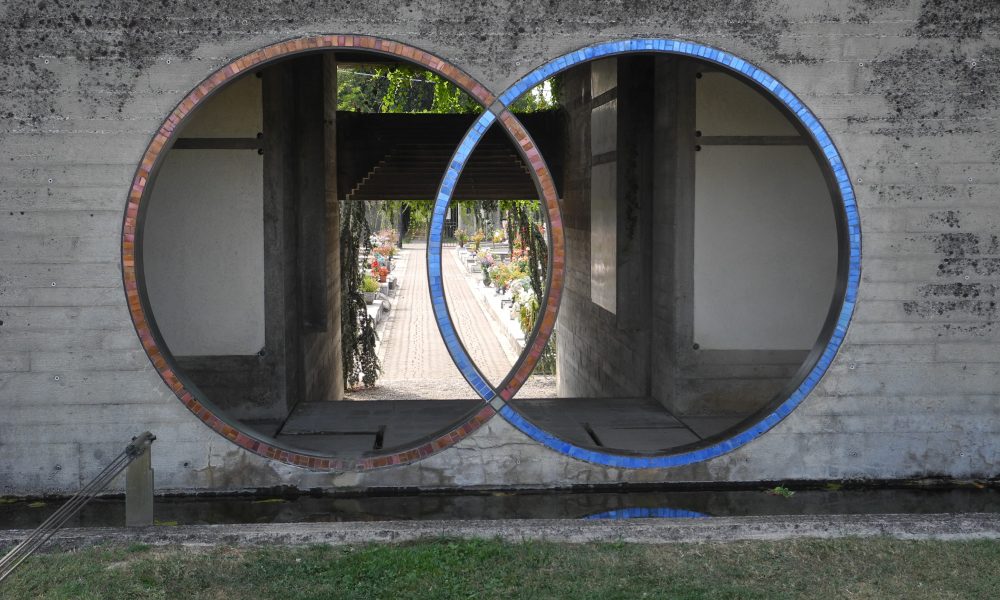

Welcoming visitors are the propylaea: the monumental entrance to the area, connecting it with the rest of the cemetery. Beyond the threshold immediately appears the strongly symbolic motif of the two intersecting rings, one red and one blue, symbolizing the bond between the Brion spouses. Interestingly, when viewed from the opposite side, the colors of the rings maintain the same orientation, blue to the right and red to the left; thus, each ring is both blue and red depending on the side from which it is viewed, doubling the concept of union. This circular opening also serves as a window onto the lawn behind, from where one can choose between two paths: one to the right, narrower, dedicated to the isolation of the meditation pavilion, and one to the left leading to the rest of the complex, to the lawn where the sarcophagi rest, and to the tempietto.

Finally, we come to the tempietto, a place full of significance, from the circular opening with small cuts on the sides of the base revealing its true nature: an omega, the end of everything, but also the final union of the two rings that come together as one. Other elements of interest are the marble doors and windows, typical of Scarpa’s lexicon, reminiscent of the windows of the Basilica of Torcello where the shutters are made of marble slabs. It’s also worth lifting one’s gaze above the altar to admire the complex execution of the ceiling, crafted like a pyramid with small steps, where concrete flows into the wooden covering.

Undoubtedly, this Monument is a culmination of Scarpa’s work, where he could bring together not only all his ideas and expressiveness but also the extremely high level of craftsmanship required to realize them, evident, for example, in the marbles, mosaics, and formwork used to obtain these figures from cast concrete. It’s undoubtedly one of the works of which Scarpa was most proud and satisfied; in fact, as reported in an interview shortly after its completion, he appreciated how visitors, with their children and dogs playing and running freely, experienced that space not only as a place of mourning but, above all, as a place of joy and serenity, according to his and the Brion family’s desire. It may thus seem only natural that Scarpa carved out a corner of his own between the Monument area and that of the cemetery, as he said, “in nobody’s land,” to create his own burial site: a simple horizontal slab with bronze decorations, under which he is vertically laid to maintain the fundamental quality for him, that is, the form. This will took place all too soon, as Carlo Scarpa will die in 1978, the same year as the completion of the Brion Tomb.

The Monument and the movie

Denis Villeneuve, with his production designer Patrice Vermette, a long-time admirer of Scarpa’s work from whom he drew much inspiration, opt for a very particular aesthetic for Dune, both for the buildings and for the means of transport. Across the various examples, three basic concepts are shared: essential and elegant geometric shapes, layers of decorations adorning them, such as in the interiors of buildings or in the details of mechanical nature, and finally a natural or historical inspiration, seen in ornithopters modeled after dragonflies or in the buildings on the desert planet Arrakis, reminiscent of stepped pyramids. These characteristics contribute to the film’s narrative, as they engage the viewer: iconic shapes are easy to remember and convey an immediate idea, while the decorative aspect serves to entertain the visual aspect so that the viewer feels that these places are real and lived-in, not just a simple set. Finally, natural and historical references are included to prevent the viewer from feeling lost, to give them something to anchor their mind to, and because, even within fiction, humans remain just that and maintain a natural connection to their past.

The Brion family was initially reluctant to grant permission to film in the complex but were convinced upon noticing the Scarpa references in Dune Part 1,a film that earned Vermette an Oscar for production design; therefore, for the production designer, it was the closing of a circle to be able to film the sequel in a place so significant to him that he couldn’t hide his emotion during the first visit, having also had the opportunity to visit Scarpa’s tomb. It is clear, therefore, that the Brion Monument lends itself perfectly as a setting, with the additional benefit of being a place actually lived in, thus integrating seamlessly with the aesthetics of the rest of the film. This is also an excellent testament to Scarpa’s work, as he succeeded entirely in his intent to create something truly close to eternity, something that manages to express itself and engage with the visitor not only in the 1970s and in the present, but also it would not be out of place in a distant future, just as classical architecture remains expressive even now.