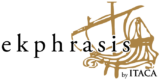

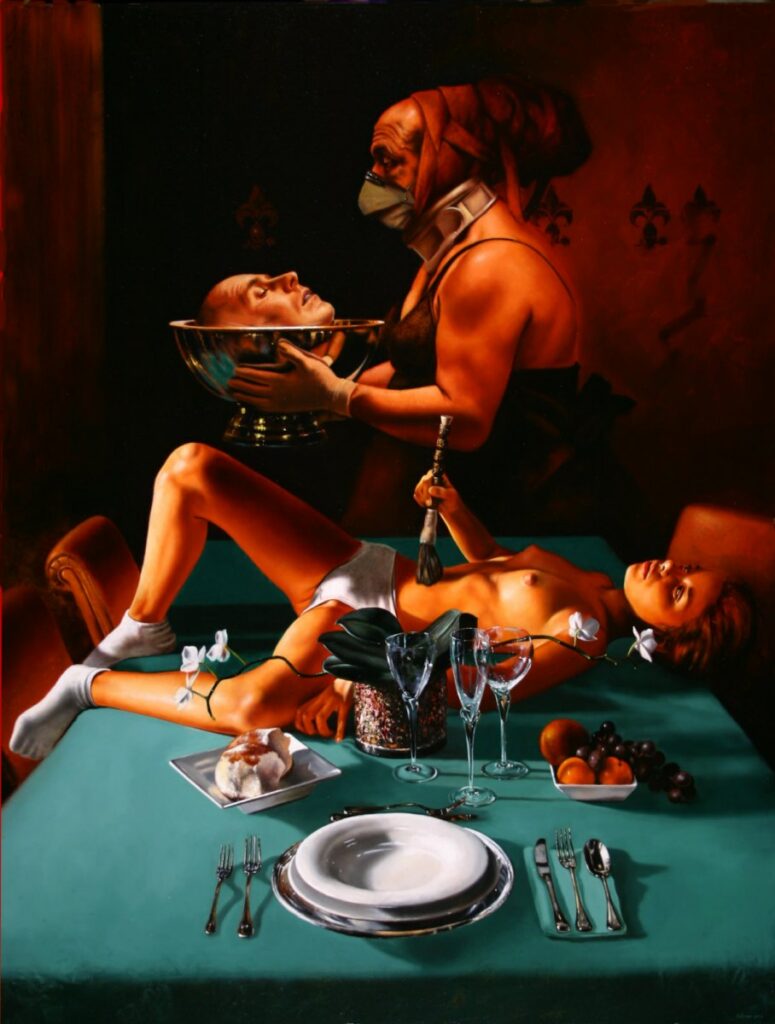

An Annunciation in which the Virgin and the Angel toast happily with two glasses of red wine; a Salomè that seems to offer herself to the viewer as the main course of a macabre meal. These are some of the subjects -disturbing only at the first glance- that we find in the paintings of Satuno Buttò.

A personal exhibition entitled Picta Mentis Revelatae, curated by Massimo Pinotti, inaugurated on 10 December at the MAD gallery in Mantua and will be open until 30 December.

The artist was born in 1957 and his training path can be segmented into three macro-sections: the first corresponds to the adolescence when, strongly attracted to art, he enrolled at the Art School and learned the classical painting technique and the study of the model. From this approach generated that passion for the human figure and portraiture that would become a landmark of his work.

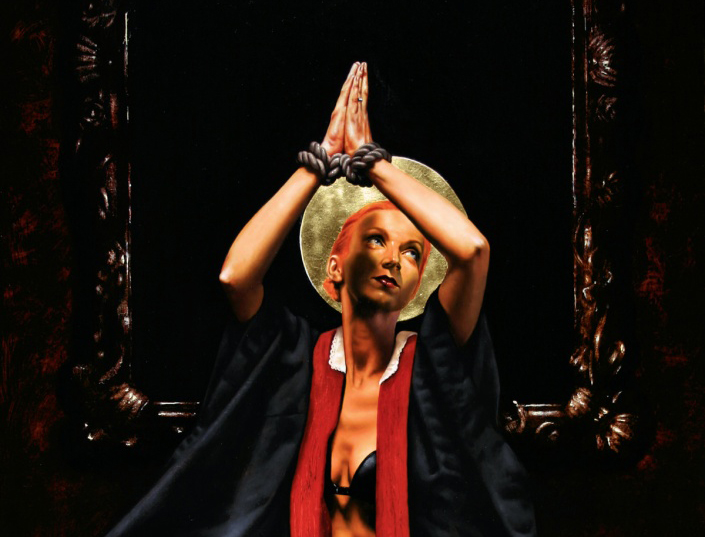

The second stage of Buttò’s journey is perhaps the most significant: the study period at the Venice Academy of Fine Arts, where he claims to have lived “an initiation in cultural terms”.

Driven by the typically youthful nature in the development of a desire to emerge among peers, and by the will to experiment that is inherent in each artist, the young man started to feel the classical painting too tight.

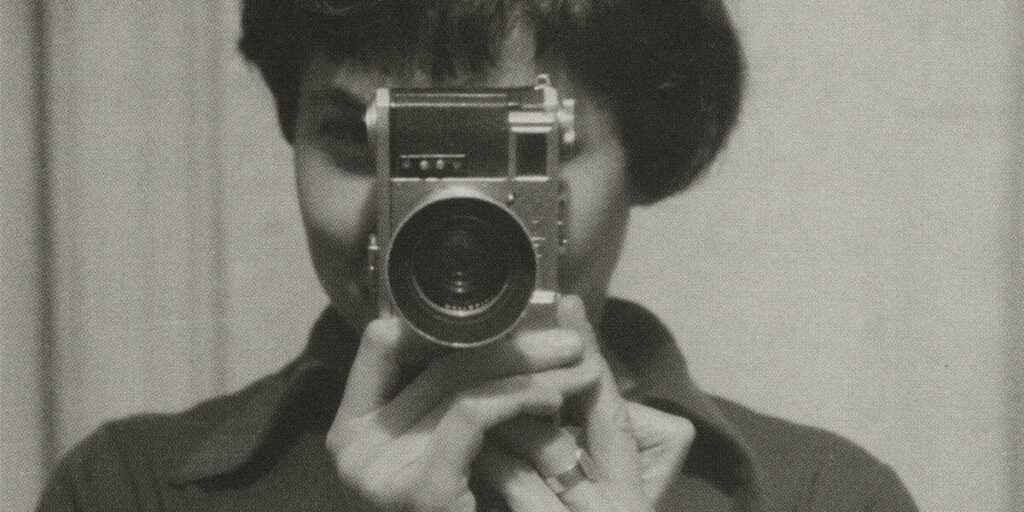

Struck by conceptual art, which allows to shift his attention from the technique and the material to the meaning, Saturno began to experiment with new techniques including photography and video. But what will mainly condition his artistic career is the 70s Body Art, developed in a period when artists, suffering against an art increasingly linked to the economic sphere, chose to put at the core of their practice something that could not be commercialized: their own body.

It is precisely this relationship with the body that fascinates the artist who will always have its representation as a focus in his art.

In particular, we can see a relation with the work of Gina Pane, whose poetry is based on the use of the body as a medium and above all as a tool to react to the stereotypes imposed by society. In some of her performances, Gina Pane self-inflicts wounds to give voice to a suffering that represents that of all women, as if she was a modern Christian martyr. At the end of her career the French artist created installations that often referred to saints and martyrs, inspired by Renaissance masters, as in the case of Saint George and the dragon (1984-85).

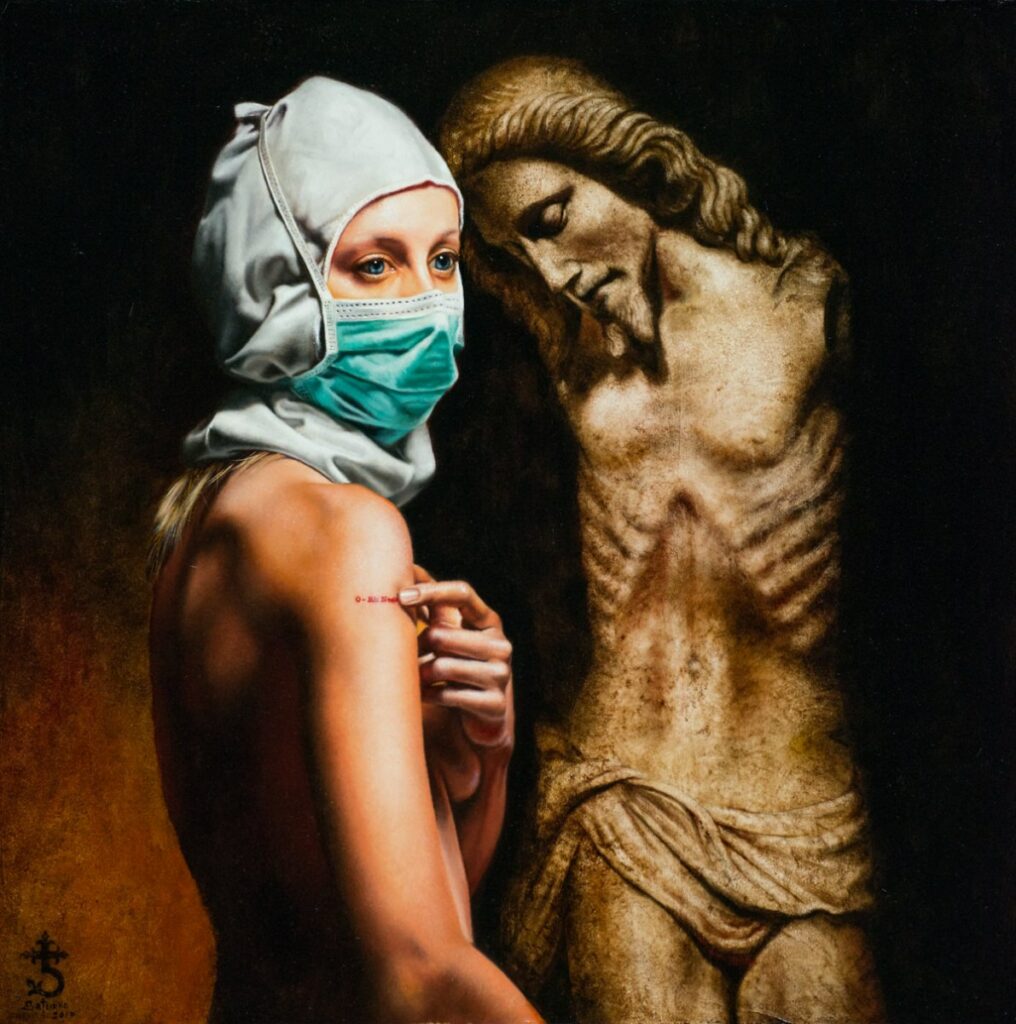

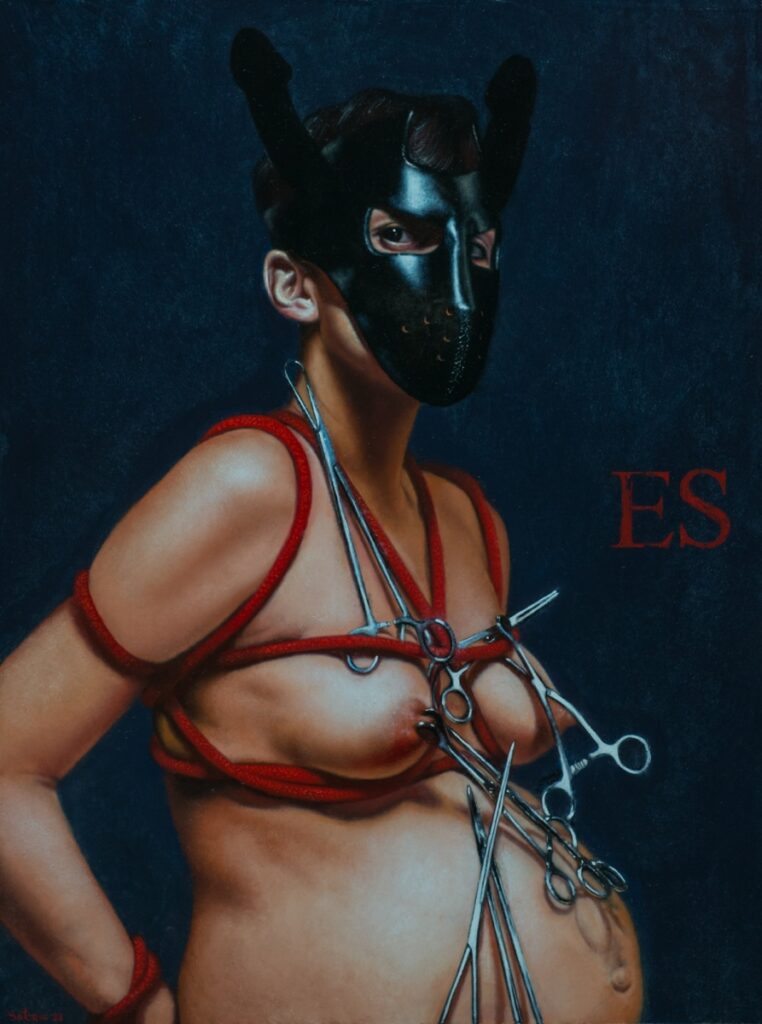

As in the case of pane, also in Buttò’s works there is a deep and personal spirituality found not only in the explicitly religious subjects, such as the aforementioned Annunciation (2017) but also in paintings that recall the sacred thanks to their composition and iconography. In Hieratic Selfie (2018) a contemporary saint with a veil on her head has an aureole composed of surgical scissors while her elbows rest on a windowsill that clearly referees to the stylistic exercises of the early Renaissance; in the background of ORH Negative (2019) is depicted a dead Christ.

The last part of Buttò’s path consists in more than a solitary decade that the artist spent in his studio honing his technique until the publication of his first monograph in 1993 “Portraits from Saturn: 1989-1992”. In this long period of reflection the artist understands that the best way to express his poetics is to recover the technique of painting and combine it with those suggestions of conceptual art and body learned during the academy years.

Thus the mature art of Saturno Buttò is characterized by a continuous coming and going between present and past that causes in the viewer some short-circuits. His paintings are endowed with a clarity and attention to detail that make them almost photographic on one hand, and reminiscent of Flemish masterpieces on the other. In his art he combines the ancient technique of oil on board to the depiction of extremely contemporary subjects, portraits of real people in which he comes across everyday life; and he refers to a Christian iconography in which the light that bathes the bodies is no longer divine, but that emanated from the screen.

But even more than confusing, Butto’s paintings present themselves to the viewer’s gaze as deliberately disturbing, obscene, contradictory: that same structure of the work that our historicized gaze is accustomed to associate with sacred representations now presents us completely naked bodies, exhibited without modesty, tormented by surgical instruments. Yet our gaze is irresistibly drawn to these representations, perhaps for the definition and the quality of the detail with which they are represented. Present and past, Sacred and profane, Dionysian and Apollonian dimension: in Buttò’s art this duplicity recurs constantly.

As in Gina Pane’s self-harming performative acts, or in the staging of the sacrificial rites of hermann Nitsch, Buttò provokes in the eyes of those who watch the pain, an anguish and even a sense of disgust aimed at achieving a catharsis able to free our soul from repressed instincts and taboos imposed by society.

The value and peculiarity of Buttò’s works lies precisely in the sacralization of what is traditionally considered the opposite of the divine: the human being, displayed without filters in its contradictions, vices and sufferings. Here the disturbing leaves room for a feeling of tenderness, of pity towards these bodies so real, so close to ours.

As David Lachapelle in photography, Buttò gives us, through painting, a message of hope in the possibilities of the human being. As the title of the exhibition suggests, Picta Mentis Revelatae, Buttò’s works represent the key to a new way of conceiving ourselves and making peace with our contradictions.