Let’s make a basic premise right away: reading Stefano Benni’s The Bar Under the Sea is one of the best choices one can make.

To describe it as briefly as possible, a man casually stumbles into a bar under the sea, meets its rocambulistic patrons (a few among them: the blonde, the invisible man, the black dog), and listens to the story each of them offers. Ranging between different narrative styles, characters, and settings, Benni plays by adopting the narrative device of an exceptional, nonexistent place and offers structure to what would otherwise be a simple miscellany of short stories with no connecting thread.

The bar under the sea offers itself as a gathering place, makes itself “set” and grants the necessary space and opportunity for the exchange and meeting of people – making concrete a possibility for the cohesion of the stories that come to intertwine; like the Florentine villa of the Decameron, or the saloon of Star Wars, the Wunderkammer – here converge stories of acquaintances and outsiders, so different and distant from each other, that otherwise they would never have connection, a way of bonding, of being exhibited.

This image suggested by Benni has stuck with me so much that it has become a personal key in the way I identify places. One does not need an absurd place like a bar under the sea to enjoy and appreciate the stories of other “crossroads” places.

On this particular occasion, to become my object of study was the La Fenice Theater in Venice; I do not deny it, purely by chance. Indeed, there are few people more precise and fond of anniversaries than a classical music enthusiast, and it just so happens that 2023 marks 200 years since the premiere of Rossini’s La Semiramide, as a good cellist friend of mine was keen to point out. A brief search was enough to reveal that the premiere was held at La Fenice and put the flea in my ear.

Music – art, more generally – is a collective, contact experience: it is only natural that the place used to house it should be designed specifically to serve this use. It is easy, therefore, to think of the theater as a solemn, untouchable, sacred place; after all, it is also that. However, it is people who make theaters, and it is always people who bring stories to life, including the most curious ones. The very birth of La Fenice starts from a collectivity – or rather, from the shared desire of a collectivity – in this case identified with the Nobile Società dei Palchettisti (Noble Association of Box-holders).

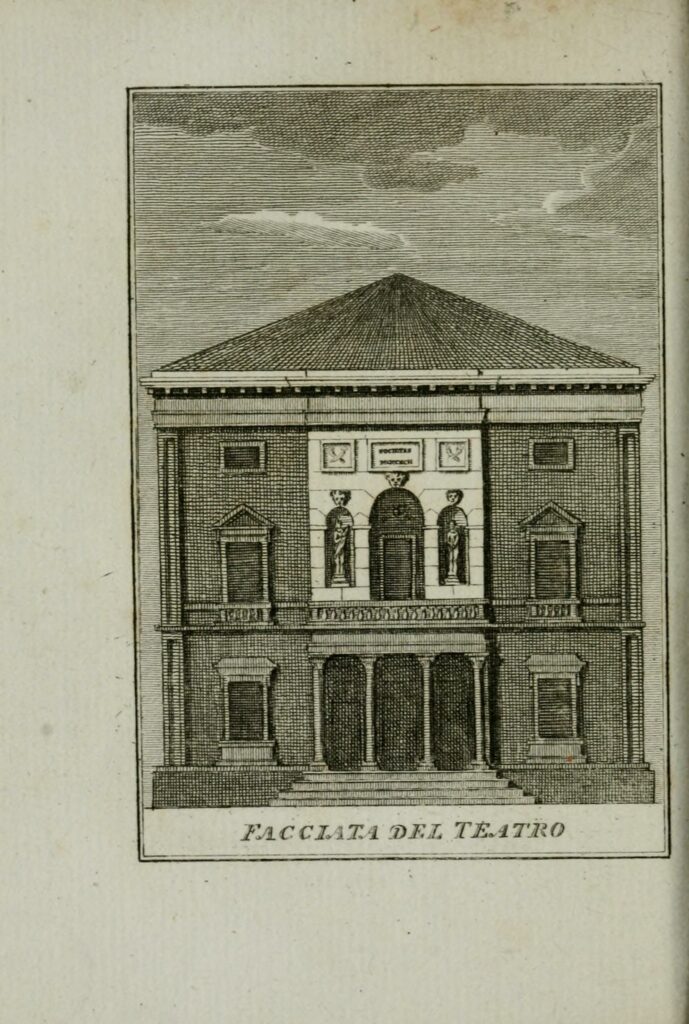

In the 1700s, the lagoon city was home to seven theaters, including the Teatro di San Benedetto. Rebuilt after a fire in 1773, the Society – owners of the theater – entered into administrative disputes with the Venier family, owners of the land, to whom they had to cede the building. This prompted them in 1789 to initiate a call for bids for the design of a new theater. On May 16, 1792, after years of criticism, including satirical mottos and even sonnets directed at the construction work, one of the most prestigious theaters ever opened its doors. Christened with the name “Fenice” (“Phoenix”), the Noble Association of Box-holders seeks to begin again under an auspicious sign.

The theater established itself and over the course of a little more than two centuries hosted and connected some of the most important personalities in the musical artistic field; to name a few: composers such as Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini; Igor’ Stravinsky, Sergei Prokof’ev, Benjamin Britten – singers such as Maria Callas, Luciano Pavarotti, Renata Tebaldi, Franco Corelli. One could spend days unearthing and delving into the intriguing stories of this artistic community, often with an almost legendary flavor. It might be useful, then, to make a distinction into two groups.

Some stories come to life at the place, thanks to the place: these are the tragedies and/or triumphs of the world premieres. These are sometimes particularly famous episodes, which are remembered and remain a fundamental part of the story of an opera’s fortunes (suffice it to recall how its anniversaries are still counted, as proven by my cellist friend mentioned earlier).

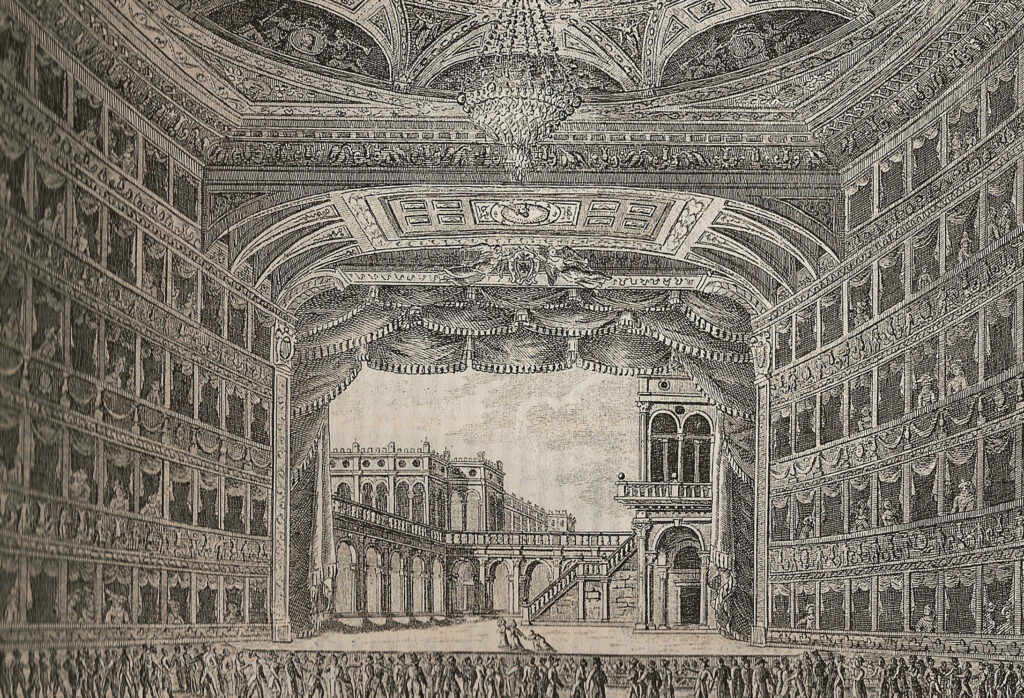

One example among all is worth mentioning: Giuseppe Verdi. The composer brought five premieres to La Fenice Theater, including two of the three operas of the renowned “popular trilogy”. Famous is the resounding success with which Il Rigoletto was received in 1851.

Even more famous, perhaps, is the fiasco that accompanies the second – and the fact that this fiasco involves La Traviata itself, an opera that is now among the best known and most widely performed in the world. (Just to present a curious fact and reiterate how these stories constantly intersect: La Traviata would achieve success the following year, in 1854, at the Gallo Theater, formerly known as the Venier Theater, and before that known as the Teatro di San Benedetto. Yes, that Teatro di San Benedetto).

Then there are the stories that people already carry with them – like the patrons of the bar under the sea of Benni. It is fascinating here to get a glimpse into the lives of singers, intense characters often surrounded by this charismatic aura, capable of characterizing an era. La Fenice has seen performances by Isabella Colbran (Rossini’s wife), Giuditta Grisi, Giuseppina Strepponi (Verdi’s companion), voices such as Giuseppina Grassini (one of Napoleon’s most famous lovers). One of the key figures, of all of them, is undoubtedly Maria Garcia Malibran. A very talented soprano, painter and composer, she is remembered for her vitality and details such as her famous light gray gondola in which she used to make her way to the theater. She was so loved, to the point of seeing her own name affixed to the Teatro di San Giovanni Grisostomo “Malibran“, today the second seat of La Fenice.

Having described its characteristics as a locus-croix of experiences and stories, it is important to remember that it is, after all, a physical place. A real environment, which throughout its history has seen renovations, adjustments, tastes of different eras, as well as technical innovations. Special mention should be made of the royal box, provisionally prepared on the occasion of Napoleon Bonaparte’s visit and later set up permanently.

It is 1996 when La Fenice burns for the second time since its founding. The second, that’s right. “Phoenix,” which was supposed to be an auspicious name, seems instead to reconfirm itself a case of nomen omen in its most negative variation. It is easy to recall with somewhat bitter irony how this had been the same fate of the Teatro di San Benedetto.

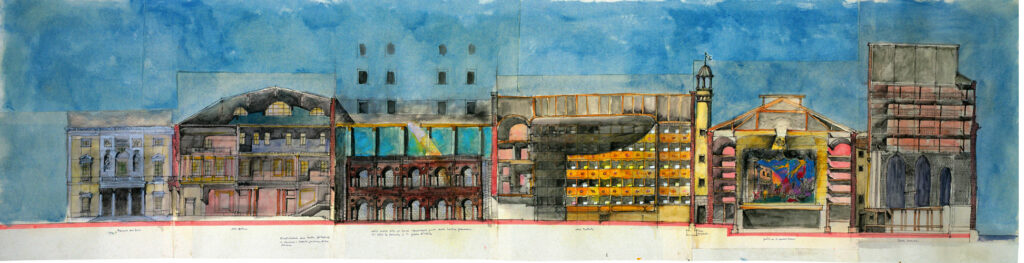

Under the motto of “as it was, where it was” – already adopted for the bell tower of San Marco‘s – an invitation to tender is announced for the reconstruction of the theater: the winning project is by Aldo Rossi. (Impossible not to notice how this, the rebirth project par excellence, corresponds to Rossi’s last project, who passes away before it is terminated).

This is not the first time that the well-established architect and architectural theorist (the first Italian winner of the Pritzker Prize in 1990) has realized a project for a theater in the lagoon: in 1979 the Biennale had already seen the Teatro del Mondo, a floating theater “linked to the water and the sky” of which Rossi particularly appreciated “its being a ship and like a ship undergoing the movements of the lagoon”. In this particular context, however, Rossi immediately saw strong limitations posed by the aforementioned motto. Not only that, he finds it impossible to follow it to the letter: “[…] if it is possible to build ‘where it was,’ I don’t think it is possible to build ‘as it was.’ Even if this project adheres faithfully to the notice, it cannot recreate that family portrait that only the architecture of the time-and a personal imprint-can give”. His project, he explains, introduces only a few personal touches. He finally concludes by saying, “[…] we worked on the reconstruction of La Fenice not to remedy a disaster but to recreate a monument of Venice”.

Rossi seems to grasp exactly the heart of the matter: it is not possible to faithfully recreate the patina that is the result of a labor limae of different centuries, hands, heads and histories. Operating from the perspective of “monument” – while introducing some innovations – allows the theater to stay true to its path as a “crossroads place”: the space for stories that have already happened is respected, the space for future stories guaranteed. The bar is open.