Architecture is a subject that has always fascinated me. In particular, I have always been attracted by the combination of utility and beauty that characterizes it: I like things that are rational, concrete, without too many frills, but I also like things that are beautiful, indeed, I think they are necessary. One would think that for a building to be functional it does not necessarily have to be beautiful as well, yet, its appearance is fundamental because as human beings we are inevitably influenced by the environment around us.

To find the right relationship between usefulness and beauty, according to many architects, it is first necessary to study the genius loci. The genius loci, etymologically “spirit of the place”, indicated in ancient Roman religion as an entity, a deity linked to a place inhabited and frequented by man. In modern times, the concept of genius loci has been adopted in architecture to understand the relationship between a place and its identity: not only, therefore, the physical environment and its architectural structures, but also all the socio-cultural expressions, habits, and language intrinsic to a given place.

For a building to be truly useful, truly functional, it is necessary to study the needs of the individuals to whom the building is addressed, but also their dreams, their expectations in order to give them a beautiful place in which life can unfold. This is what makes architecture not a mere matter of calculations, but an art, a complex matter in which creativity, technical rigor, politics, civil commitment and a profound understanding of the human being and his context interpenetrate.

Giancarlo De Carlo, in this sense, is perhaps the architect who best represents this way of doing architecture, the ability to read the place and understand people, drawing from them reflections to be placed at the basis of the project. Representative of this modus operandi are two projects: the Matteotti village in Terni and the the social housing on the island of Mazzorbo.

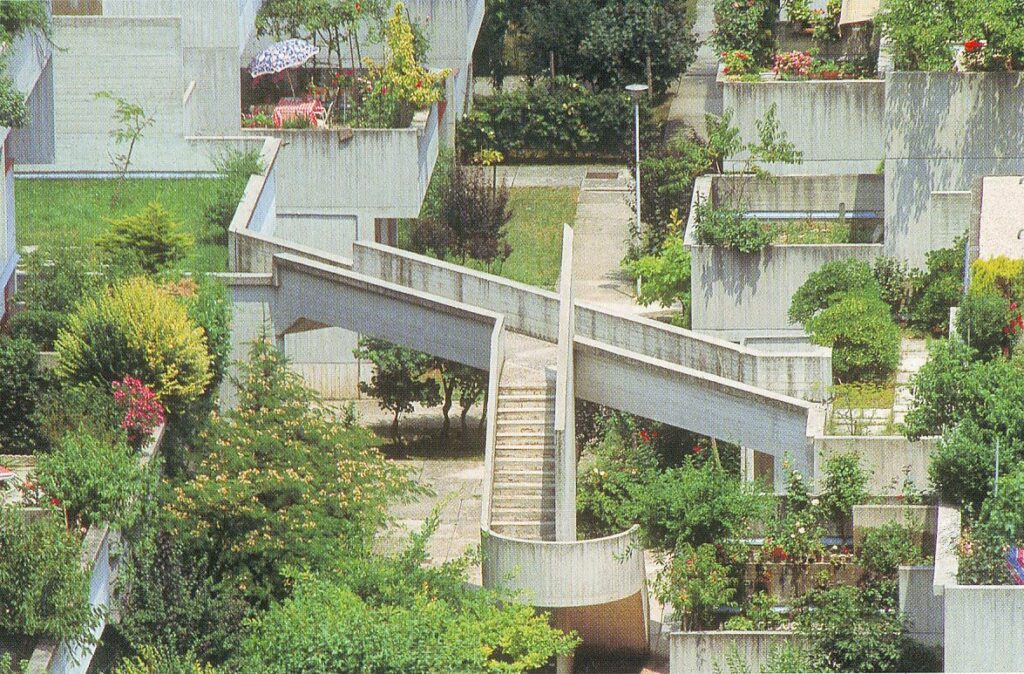

The Matteotti workers’ village in Terni is an exemplary case in Italy of a direct participation project. De Carlo in fact accepted the commission on the condition that he could interact with all the people to whom the housing was addressed, and design the neighborhood together with them. So it was that in 1969 a long and difficult process began, which ended in 1975 and saw the architect interacting with hundreds of families, not without difficulty, to understand what their wishes were.

It took some time for the architect to win the trust of the people, who were not used to being asked in these decisions, and when they finally opened up, it turned out that they demanded less than what they could have had. This is how De Carlo recalled the conversations he had with the steelworkers:

‘They were very modest. I would often ask: ‘Why don’t you have greater ambitions?’ And they would answer that they were used to not having any, because no one had ever considered them. They were used to the minimum’.

So the architect decided to make an exhibition in which he would display pictures of homes to which the future tenants could aspire. Gradually, guided by the architect, people became aware of their rights and a fruitful dialogue began in which the main need found was the presence of green spaces. The result is a neighborhood composed of 254 flats, connected by pedestrian paths, spaces dedicated to services such as a kindergarten or a supermarket, and public and private green areas that guarantee the right balance between neighborhood and privacy.

It was 1979 when the municipality of Venice adopted a plan for the redevelopment of Burano and the construction of new housing in Mazzorbo, for which it entrusted the design to Giancarlo De Carlo, then professor of urban planning at Iuav. Unlike the Matteotti village, the intervention in Mazzorbo can be defined as a project of indirect participation: the different housing way prevented from having a direct relationship with the final recipients, in fact from an urban planning point of view it was a very bare and sparsely inhabited island.

De Carlo took as his object of study and inspiration the settlement pattern of Burano, to which Mazzorbo is connected by a footbridge, and the Venetian islands in general. He thus proposed the typical concatenation of dwellings unraveling along the canals, interspersed with campi and campielli conceived as the continuation of the private space of the house, aimed at stimulating and welcoming the social life of the inhabitants.

As far as the aesthetics of the dwellings were concerned, he chose to always refer to the example of Burano but in a non-mimetic way, in his opinion in fact:

“in order to be coherent and decisive, new forms must be strictly appropriate to the contemporary context, that is, they must be modern forms. Therefore, positions of mimesis or rupture do not make sense, because true concreteness lies in the search for a dialectical coherence in which the new forms have the capacity to assume contradiction and, at the same time, the strength to contest it”.

For this reason, the architect used certain expedients such as the protrusion of the stairs from the building with the intention of recalling the chimneys protruding from the façades of Venetian houses.

However, he took up the delicate pastel colors of the houses on the neighboring island, which are altered by the sparkle of the lagoon light and its reflections on the water, thus harmonize the new settlement with the typical atmosphere of the lagoon north of Venice. Thus, we see how the consideration of the genius loci made it possible to create functional buildings that truly responded to the needs of their inhabitants and were also beautiful, that is, suited to their context.

However, another interesting aspect also emerges from these projects: the social responsibility of an architect who is concerned with the quality of life not only of individuals, but also of the community, paying particular attention to gathering spaces, meeting places and the location in these structures of useful everyday services such as small grocery stores or kindergartens.

As in Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation or in the grid structure of the city of Barcelona, there is a tendency in De Carlo’s case to consider small groups as real city nuclei, with the desire to provide them with all the services and spaces necessary for sociality. Behind the solutions designed specifically for certain places there is therefore a broader consideration of the idea of the city.

At a time of the economic boom of the 1970s and 1980s, the result of the recovery after the Second World War, cities began to expand often without logic. The growth of cities and the increase in population inevitably led architects to reflect on the idea of city and society, thinking of solutions in which that idea of community, of neighborhood, typical of small Italian towns, could live on.

Today, some 50 years after the construction of De Carlo’s buildings, they are still in good condition, although it is sad to see that some of the spaces aimed at socialization are not used, or that the food services or kindergartens have been closed.

Clearly, society is different and different people have taken over from those for whom the projects were originally designed, and with the economic crisis, it is difficult for these small establishments to survive with a small user base.

Is the type of neighborhood De Carlo envisaged, especially from the point of view of relations between community members, still valid? Is it suitable for our society

Beyond the changing needs of our time, some of De Carlo’s tendencies have certainly been followed, especially outside Italy. I am thinking for instance of Cobe, a group of young architects in Copenhagen founded in 2006. Similarities with De Carlo’s approach can certainly be seen in their attempt to understand the entire city of Copenhagen as a project area and, therefore, to think of each intervention not as something extraneous, but as something deeply embedded in the context. In particular, the group of architects gives fundamental importance to the needs of the citizens, involving them in the so-called “Cobe sessions“, meetings open to the community whose objective is both to present the new design possibilities, and to collect the opinions and comments of the population, in order to understand their needs and increase their awareness.

Clearly, the situation is different from the 1970s and the Cobe group is confronted with new and pressing problems, such as environmental impact or accessibility, but it seems that the need to create spaces for the community to gather remains essential.

“The belief in the importance of architecture is based on the idea that we are all different people in different places and on the conviction that it is architecture’s task to give us a vivid image of what we could ideally be”.

In this way Alain De Botton in his text Architecture and Happiness reiterates once again the importance and power of architecture: its ability to influence our experience, encouraging a more democratic and communal way of life.